WAITING FOR THE BIG ONE ON THE BC COAST

WAITING FOR THE BIG ONE ON THE BC COAST

by William Thomas

The first warning will come from the dogs. Every mutt within earshot will be barking mad because they’re hearing fast-travelling, high-frequency compression waves you can’t detect, radiating outward from the Cascadia Subduction Zone 75 kilometres off Vancouver Island’s west coast. This 700-mile collision between the eastward-trending 90,000 square-mile/40-mile-thick Juan de Fuca Plate and the massive North American slab underlying this continent packs much more destructive force than Hollywood’s beloved San Andreas Fault.

“Cascadia can make an earthquake almost 30-times more energetic than the San Andreas,” boasts Chris Goldfinger, professor of geophysics at Oregon State U. Together, these faults make a 1,500-mile-long zipper along North America’s west coast.

What could possibly go wrong if Cascadia comes unfastened? The Boxing Day quake off the coast of Sumatra on December 26, 2004 “unzipped a 1,300-kilometre subduction zone under the sea floor, generating killer waves that took more than a quarter of a million lives in 14 countries,” answers Margaret Munro.

BC emergency planners anticipate a similarly-strong megaquake will kill 10,000 people in Vancouver alone, and injure another 30,000.

Thirty-seconds go by while you wonder what’s freaking out the dogs. And why everything else has gone so expectantly still. You might have another 60 seconds to find cover.

Or no more time at all.

Like a low ocean swell on land, long, undulating surface waves arrive. You can tell because you’re on your hands and knees like a wide-eyed infant and the ground is nodding up and down and wagging side-to-side. If you’re inside, cranium-threatening objects are hopping off counters, shelves and the desk you’re crawling under.

Because you invested the time to read these linked articles, you recall there’s a 5% chance any earthquake is the foreshock for something bigger. (Chileans recently found this out.) This is not one of the 2,500 minor tremors under magnitude 4.0 that sway what insurers call “highly seismic” BC every year. You know this because the shaking hasn’t stopped.

Reflexively, you check your watch:

1:19

TIME = MAGNITUDE

Just passing 10 seconds, which means magnitude 6.3. The 6.3 near Christchurch, New Zealand in February 2011 was too shallow to trigger a tsunami. It did however, notes John Clague, a long-time geologist and professor in SFU’s earth-sciences department, cause “$20 billion damage and kill a couple hundred people.”

The shallower the epicentre, the more damage results. And in a sixer, sediments turn to slime.

The Christchurch quake wasn’t huge, Clague emphasizes. “And yet it caused so much liquefaction-related damage, and we could certainly expect a similar type of damage pattern in Richmond and parts of Delta,” where the Fraser River has been laying down sentiment since forever.

Meaning?

“You have to think of the infrastructure at risk there,” Clague continues. “There’s the airport; there’s the Delta-port; there’s the Tsawwassen ferry terminal; there’s electrical cables that deliver a significant chunk of Vancouver Island’s power – they cross the Fraser Delta and go across the Strait of Georgia… These are huge things, I think, in terms of economic infrastructure at risk.”

And now you know that “vigorous aftershocks in the magnitude 4-5 range” invariably follow earthquakes of magnitude 6 or larger.

At 15-seconds, you’re in a magnitude 6.9. We’re talking 63 dead, $6 billion damage, Loma Prieta, California, 1989.

30-seconds of strong shaking and you know you’re in a much stronger mid-7.

One-minute of shaking puts you in the high-7s.

Two-minutes bring you into the 8s.

Three-minutes of rippling ground and swaying structures signify the high-8s.

Four minutes! Welcome to the Really Big One: magnitude 9.0 on Richter’s deceptive scale. The fridge decides to leave and starts jitter-bugging with a willing cabinet, until both topple over like the trees and buildings around you. It’s not just the surging surface waves that’s knocking things down. The ground itself is turning to mush.

Six interminable minutes of rocking and rolling replay Japan’s Great Tōhoku calamity of 2011. Those groans and cries for help are coming from your family, neighbours and co-workers. And they’re forcing a calculus as brutal as dogging a hatch on drowning shipmates to save the foundering ship of self. Because if you’re getting back to your feet on any BC coastline unshielded by Vancouver Island, you have at most 20-minutes to reach ground as high as you can get.

Maybe 10. Forget driving anywhere. You need roads, bridges, on-ramps and no traffic jams for that.

Twenty minutes after the quake's initial surface waves, anyone on a BC coastline not sheltered by the 460-kilometer-long bulk of the Big Island will be looking up at the first great ocean waves. You will know they're coming when all the elephants stampede for higher ground (at least they did in Thailand), and seawater sucks back from coves and beaches, leaving ambushed fish flopping on the exposed mud.

Too late now! Your only chance is to find the closest standing building and gain its upper floors. Remember, more giant waves will follow in succession. The resulting floodwaters will not immediately recede. Steep-sided inlets will squeeze onrushing tsunamis at least 10-metres higher.

EPIC FAIL

The Richmond dyke has failed and the portions of any Gulf Islands resting on ball-bearing-like shale have slid into a washing machine called the Salish Sea. Familiar surroundings are bewilderingly unrecognizable – jackstrawed trees, jumbled masonry, rubble and flattened homes everywhere you look.

The downed powerlines aren’t dangerous because there is no hydro anywhere. It will take years to restore underwater cables, power poles, generating stations and transmission lines to the Gulf Islands. Wells have caved in, and coastal BC will remain without basic services long enough to add the provinicial economy to the wreckage. Cities like Nanaimo, Victoria and Courtenay are now facing up to a three-year haitus without functioning water mains and sewage.

In a megathrust magnitude 9, writes Pulitzer Prize winner Kathryn Schulz in her National Magazine Award feature, “The Really Big One”: The northwest edge of the continent, from California to Canada and the continental shelf to the Cascades, will drop by as much as six feet and rebound thirty to a hundred feet to the west – losing, within minutes, all the elevation and compression it has gained over centuries. Some of that shift will take place beneath the ocean, displacing a colossal quantity of seawater.

If the epicentre is offshore in the Cascadia Fault, residents of Tofino and Ucluelet are racing incoming walls of seawater up to 30 metres high.

But not in the Gulf Islands. On January 23, 2018, at 12:31 on a snow-covered night, a 7.9-magnitude earthquake rumbled out in the Gulf Alaska at a depth of about 16 miles, 280 kilometers southeast of recently clobbered Kodiak Island. Around 01:45, a tsunami alert went out for all B.C. coastal areas, the west coast of Vancouver Island and the Juan de Fuca. It did not include the Strait of Georgia.

“For a tsunami to hit Vancouver, the earthquake would need to be either under or east of Vancouver Island,” assures Vancouverite, Will Cee.

In 2017, Nanaimo was tickled by a 1.7.

SWARMED

“The last significant quake to rattle the West Coast was a magnitude 6.5 tremor that struck about 50 kilometres off the west coast of the island in September of 2011, swaying high-rises as far away as Vancouver, Kelowna and Seattle,” reports the CBC. The seabed close off the north, west and south shores of Vancouver Island regularly hosts swarms of three or more earthquakes measuring from 1.8 to 5.3 in magnitude.

"In the very thin crust that we have out there off our west coast of Vancouver Island, it often fractures in a series of small earthquakes,” explains Pacific Geoscience Centre Seismologist Gary Rogers. Activity is concentrated along the Raveer Delwood Fault, located about 200 km offshore.

“They often go on for days,” Rogers reassures us. “There's been a lot of smaller ones, so eventually they'll wind down, but typically, what we've seen in the past is that most of these swarms last a few days to a week or so.”

SHOULDER-TAPS

“It's a wonderful reminder for everybody to, perhaps, take a moment, and look back and examine whether or not they are well-prepared for the strike of an earthquake,” suggests Dr. Honn Kao, a research scientist with Geological Survey of Canada. Don’t forget, Oregon is the most earthquake-prepared region on the entire west coast. More than 1 in 5 persons living there is 65 or older. Or disabled.

The Gulf Islands’ aging demographics can’t be much different.

DISTURBING SEDIMENTS

“What if this area failed on Roberts Bank? What would the wave look like?” wondered marine geologist Brian Bornhold. In a megaquake, could underwater landslides mirroring the many taking place around the steeply sloping Georgia basin, trigger surprise tsunamis inside the strait?

After studying underwater landslides for most of his career, including 25 years with Geological Survey Canada, Bornhold says, no.

Seafloor slope failure will not occur, concurs John Clague, a veteran geologist and a professor in SFU’s earth-sciences department. Looking at the suspect sediments here, “There is no basis for a deep-seated failure being likely on the Fraser Delta.”

Referring to the Really Big One, he adds, “We had one of those in AD 1700 and it, apparently, didn’t cause that kind of failure.”

Earthquake mapping and profiling reveal that this ancient quake and ensuing tsunami uncannily mirrored the magnitude 9.2 Boxing Day catastrophe in the Indian Ocean.

JANUARY 26, 1700 9 PM

A nearly 1,000 km-long rupture opens along the Cascadia Fault, as that downward-buckling plate instantly slips some 20 metres. First Nation’s oral history relates how the resulting magnitude 9 earthquake shook the Pacific coast like a thunderbird in the mouth of an orca – for minutes. The legendary struggle was felt in Manitoba.

“It was wintertime and they'd just gone to bed," recounts Natural Resources Canada seismologist, Alison Bird. According to oral tribal history passed down through seven generations: “They sank at once, were all drowned; not one survived.” In Washington State’s inundated Neah Bay, survivors found canoes hanging from the trees.

After erasing the Huu-ay-aht village of Anacla in Pachena Bay, about 300 km northwest of Victoria – and nearly everyone and every dwelling on that coast – the tsunami raced 4,800 miles across the Pacific faster than a modern jetliner.

“About nine hours later, a tsunami the height of a four-storey building hit the Japanese coast,” Dirk Meissner related like a latter-day eyewitness in the Canadian Press, “destroying all in its path.”

NO BIG TSUNAMIS IN THE SALISH SEA?

Speaking of massive earthquakes not splashing blockbuster-size tsunamis through BC’s inland sea... “We’ve had maybe six or seven in the past 3,500 years or so, and we don’t see that, so I would say that it’s unlikely,” Clague concludes.

Any incoming tsunami attempting to make a hard turn north or south before moving through the Salish Sea will rapidly weaken. In the protected Georgia Strait, “only small waves are likely to be experienced,” promises John Cassidy, an earthquake seismologist with Natural Resources Canada.

On the other hand, the CBC reports, Victoria can expect a tsunami of between two and four metres within 75 minutes.

On the other other hand, if the city of Vancouver finds itself being carried east on the back of the Pacific plate 75 miles below, Gulf Islanders can look for 20 to 30-foot surges coming ashore.

The chances of this happening are nearly nil.

WHOSE FAULT?

But not quite.

John Cassidy, an earthquake seismologist with Natural Resources Canada points to a previously unsuspected fault running “right through downtown Seattle.” Shockingly discovered “about 15 years ago,” this unzipped zipper “runs right up to the surface.”

The Lower Mainland could be hiding similar surprises, Cassidy believes. Shallow earthquakes expose hidden faults. But…

“We’ve been recording earthquakes for a long time in British Columbia, for more than a hundred years. And the shallow earthquakes, there are very few of them.”

Does tsunami-capable geology undermine this gleaming metropolis? You can't tell by looking. In this primeval province of crushing glaciation, steadily eroding rainfall, and riotous vegetation, Vancouver’s Secret remains coy.

John Clague goes on to describe Seattle’s cleaving as “a known active fault,” worryingly encumbered with “a history of large slips during postglacial time.” Before anyone can think, Glad I don’t live there, he adds: “There’s no reason to think that these active faults end at the international boundary.”

What is needed, BC seismologists agree, are expensive overflights of Metro Vancouver using LIDAR laser imaging to probe and map previously unsuspected active faults. Until the feds come up with the cash, a silent assassin could be undermining a stunning oceanside city that, when approached under sail from across the strait, rises like a modern-day Atlantis from the Salish Sea.

HOPEFULLY, WHATEVER

I know. I know. We’ve seen the movie and heard it all before. When it comes to fostering complacency, out-of-sight subduction zones are really seduction zones.

“Hopefully it won’t happen,” is the go-to verbal shrug for those choosing to hang out under Thor's mightiest sledge hammer. What else can we do? That is, besides preparing for any number of converging climatic, geologic, economic and atomic upheavals capable of forever upending our everyday routines within months... or minutes.

Pointing to the unusual “swarm” of quakes currently taking place all around the Pacific Rim (except volcanically-bereft BC), Portland State U. geology professor, Scott Burns warns, “They may be precursors to the ‘big one’.”

But without a date circled in red on our kitchen calendars – EARTHQUAKE DAY! – how many extra tampons and granola bars should we stick in the drawer?

1 IN 3 ODDS

“The science is robust,” concludes Kathryn Schulz. “We now know that the odds of the big Cascadia earthquake happening in the next 50 years are roughly 1 in 3.”

BC’s Auditor General says the South Coast and Haida Gwaii carry the highest risk of a big earthquake. Could this July’s prolonged shaking in our geologic neighbourhood be Godzilla’s approaching footsteps? You bet your life.

PANIC NOW AND AVOID THE RUSH?

Off Vancouver Island, “every 14 months or so – almost like clockwork – there is a sudden reversal” of its eastward movement “for a couple of weeks,” relates seismologist Johanna Wagstaffe, as that obstructed, pushy plate suddenly settles in a “slow slip”.

Like Thor Jr. using his toy hammer to tap spikes into our coastal coffin, each slip builds up pressure along the Juan de Fuca and San Andreas faults. Until one day – or night – they “unzip all at once.”

“It’s something that would happen relatively instantaneously,” envisions Cal State Fullerton professor Matt Kirby.

This year, in a key seismic zone approximately 40 miles east of downtown Los Angeles, there have been more than 1,000 earthquakes since May 25th in an area less than one square-mile, “very close” to the San Andreas Fault, Michael Snyder reports.

Is our space colony coming unzipped?

“Any time you have an increase in the number of small earthquakes, you’re likely to increase the likelihood of a slightly larger earthquake happening,” cautions USGS geophysicist Andrea Llenos.

“Shaking in one part of the globe can have tremendous implications for people literally living on the other side of the planet,” Snyder corroborates. “Those living along the west coast should be deeply alarmed that seismic activity along other areas of the Ring of Fire appears to be intensifying.”

SLIM SLOW SLIDERS

How many small slips make a big one? Right now (July 21/19), all three distinctive quake zones in the Pacific Northwest are active together, as the Pacific Plate heads for Japan and the California-size Juan de Fuca Plate slides (subducts) eastwards beneath the continent-size North America Plate.

Or tries to.

The undersea faults threatening BC are smothered in sea-bottom seismographs, but Canadian scientists and their American counterparts “have detected few signs of the grinding and slipping they expected,” reports the Daily Mail.

Instead, these head-butting tectonic titans are bulging Vancouver Island upwards at an annual rate of your fingernail's growth, while simultaneously compressing eastwards a whopping 30-40mm every year.

Subsequent swarms of tiny tremors provide no safety valve, as centuries of titanic shouldering pressures continue to build along this interface.

Okay, maybe “titanic” is not the best word.

PACHENA BAY REVISITED?

“Every year we hear the same thing, that, 'Oh, the big waves are going to come, the big waves are going to come,"' says Stella Peters as she looks out on the Pacific Ocean from the wide-open beach handed down to her family as a wedding dowry. “I'm not really too worried about it actually happening,” she adds. "We seem to be on the ball when it comes to evacuating the place. Nobody left behind. All the elders, the kids, even the dogs are all taken out of here."

Kudos and deepest respect to the Huu-ay-aht people for practicing their village’s tsunami response. Unfortunately, a structure-flattening, road-blocking, middle-of-the-night, 9.0 megathursting earthquake would not fully equate to the most thorough pre-announced drill. Surrounded by flat ground, beachfront “inundation zones” are the hardest places to evacuate to safe elevations – in mere minutes – without drivable roads.

In the immediate aftermath of the Really Big One, those who linger on an exposed shoreline to dig out children and spouses, or assist grandparents and the disabled will all perish together.

Who can desert their kin? In tightly-knit tribal societies whose stories stretch back to the last Really Big One, such selfless expressions of love and solidarity seem appropriate.

Otherwise, not so much.

“We can’t save them,” Kevin Cupples says flatly. “I’m not going to sugarcoat it and say, ‘Oh, yeah, we’ll go around and check on the elderly’,” adds this city planner for Seaside, Oregon. With a Sumatra-size tsunami inbound… “No. We won’t.”

“When that tsunami is coming, you run,” insists Jay Wilson, chair of the Oregon Seismic Safety Policy Advisory Commission. “You protect yourself, you don’t turn around, you don’t go back to save anybody. You run for your life.”

Mindfull of strong aftershocks, Gulf Islanders can (99%) safely render seaside assistance without fearing a big tsunami. Expect a very rapid king tide raising water levels to, or just beyond, previous high-water marks.

Heeding their elders’ counsel, the Huu-ay-aht tribal council has constructed its new administration building high above Pachena Bay.

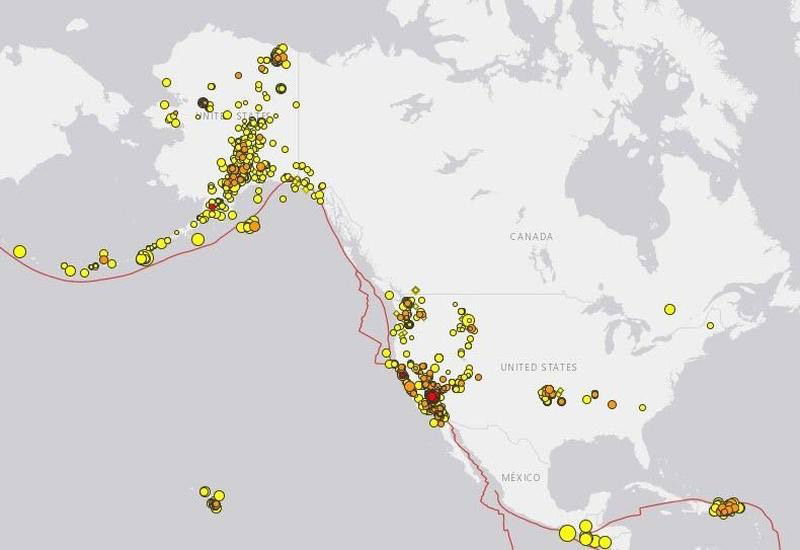

Photo Captions:

Rumbles in the West Coast Ring of Fire