CELERITY IS HER DREAMED NAME

CELERITY IS HER DREAMED NAME

by William Thomas

Celerity is her dreamed-name. Clear at last of the great northern continent, the little cutter is free to run, hunting the south from northern fjords like a falcon released from the fist. There is joy in her gait, a wild exuberance which flings rainbows of spray from the plunging lee bow. On and on and on she drives: 1,000 miles that second week; 1,000 still to run...

More akin to a light aircraft than a conventional ballasted keelboat, the outrigged 31-footer has already survived Force 10 off the notorious Washington-Oregon coast, and a full-fledged hurricane off Point Conception. Cambered decks and shoal draft enabled her to slip the heaviest punches.

Now semi-submersible outriggers dampen a violent beam swell, spilling gusts like pneumatic shock absorbers. But it is this boat's love for sail which holds me enthralled.

The Polynesians call such spirit, mana. It is a quality I recognized the moment I clapped eyes on this Kismet-class trimaran. Propped on oil drums in a Gabriola Island backyard, the partially completed orphan stood with wings outspread as if poised for flight. A workmanlike plumb bow and rapier-lean amas promised grace and speed. Her underbody was round and smooth as a dolphin's. Lord, I breathed, inhaling the intoxicating aroma of freshly sawn cedar, if she sails as good as she looks...

I could not have dreamed then how far this backyard boat would take me: through southern seas and western isles all the way to China - and Japan. Return seemed impossible. But in the late summer of 1985, Celerity swam out of dense fog and entered Victoria's inner harbor, tying alongside the same float she had departed from eight long years before.

The voyage was done; the Pacific circle completed. I wanted very much to meet Celerity's designer. I needed to know what circumstances of rearing, inspiration and obsession had led him to design such a fabulous seaboat.

The synchronicity of seafaring proved more direct than a phone call. A few days after rafting alongside a friend's houseboat, Bill Kristofferson stopped in shock, gaping at an apparition some said had been lost at sea.

In Japan's southern islands I once saw a huge sumo wrestler cradle a tiny infant with a delicacy that made her croon.

Perhaps Kristofferson grips his drafting pencil as lightly. But it's hard to imagine a flimsy Steadtler surviving long in the grip of this squat, powerful Swede. Bill Kristofferson looked more like the builder of Haida longhouses or the weightlifter he's been than the creator of some of the most fabulous seaboats ever to grace the water.

Even as I introduced myself, I sensed how Kristofferson's pugnacity has carried over into the Kismet 31. Boat and designer share the same solidity, the same straight-ahead "rightness" and competent aplomb.

"You got it right," I tell him, gesturing toward the outrigged boat that even moored never does stop sailing. I explain how Celerity averaged 165-miles a day reefed down in the Trades. "The worse the conditions, the more seakindly her motion. She's easily handled, utterly forgiving and safe as a raft in a blow."

Kristofferson smiles. He's proud of his progeny. Celerity is the smallest trimaran to complete a Pacific circumnavigation; the first multihull to make the nonstop passage from Japan to North America.

"I'm sure there were times out there," he says, looking me in the eye, "when it could have gone either way."

My stomach contracts as I recall the hurricane off Kirabati...the soul-stunning impact on the reef off Guadalcanal...the near pitchpole that night approaching Suvarov.

"Luck," I tell the stocky Swede, "counts most of all.”

Luck, and a boat whose spirit is descended from the Vietnamese and the Vikings. Rebelling against the exhausting gyrations required to "tack" and balance a single-outrigged canoe, the Dongaon culture of Vietnam invented the double-outrigger some 2,000 years ago.

The Swede who improved on their work is descended from a clan which counts generations of deepwatermen who were born and put to sea from Gotland - a 5th century Viking stronghold on the Baltic Sea.

Kristofferson remembers huge model square-riggers carved by his grandfather, a frustrated locksmith who often locked up to go fishing. Young Bill would accompany him, helping hoist the gaff on their Falmouth punt. In 1945, a five year-old boy's fascination lay not in the world's second oldest walled city, but in surrounding waters so shallow that upended brooms served as markers.

While staying with Canadian relatives, he attended high school on Texada Island off the coast of British Columbia. By the time he was 17, Kristofferson found himself constantly "fooling around with boats." He would bang a new one together each weekend, impatient to see how his ideas turned out.

A degree in Naval Architecture at the University of Stockholm was tempered by a summer voyage from Norway to Gibraltar on a 29-foot Spitzgutter. There followed three North Atlantic crossings aboard Danish double-enders, and an eight month apprenticeship working mostly on steel yachts with the Van Stadt yard in Rotterdam.

Heeding his father's dictate to "diversify," Kristofferson earned a civil engineering ticket and found work in Libya. Living like a sultan in a hot, exotic land, the young construction manager quickly fell in love.

She was the most beautiful creature he had ever seen. She used no caulking, no iron fastenings. Her teak planks were fastened with glue made from camel's hooves and she did not leak a drop. Kristofferson paid $1,000 to a Tunisian sheik for the battered 20-foot dhow, replaced the rig with a lateen from a 35-footer and pitched the sandbag ballast overboard. He lost three cameras to capsize before he learned to sail her.

The Arabs were hauling their boats for the winter when he and a companion set sail for Sicily. They soon ran into a breeze that sucked the soup from their thermos and made it painful to breathe. For 60 hours both men bailed in water up to their waists. It was the biggest blow in a decade. When they finally fetched their destination under jury rig, no one believed their port of departure.

The African adventure ended in a pitch-dark warehouse in 1964. Packing sulfa into deep stab wounds, Kristofferson abandoned his new Mercedes and all of his possessions and caught the next plane to Canada.

He ended up managing several shipyards on the west coast. At Port McNeil he helped build seven Carius 37's. At Silva Bay there were always problems with SORC boats that leaked or wouldn't steer.

It was wonderful experience. Fate, you might say. After he met and married a strong northwest coast woman named Ruth, kismet next led him to a bright red Piver Nimble tied to the Pender Harbor government wharf.

"What is that?" Kristofferson yelled to the trimaran's startled owner. My God, the budding designer thought. You can leave the ballast behind!

He knew instantly that he wanted to design trimarans. But he had no idea how they worked. When he started searching the coast, Hedley Nicol's beamy main hull was the only trimaran that looked like a "real boat."

He and Ruth spent most of 1968 building and modifying a 27-foot Vagabond. After launching, Kristofferson would lie for hours in the bow nets watching the wave interaction in the tunnel between the hulls. By the time their second child was on the ways, he decided to design a family trimaran radically different from those which had come before.

Instead of following the narrow length-to-beam ratio favored by multihull designers over millenia, Kristofferson drew a cold-moulded load carrier like Nicol's. But unlike Nicol and Piver, who favored clipper bows, the stem that emerged under Kristofferson's hand was very nearly vertical. With a waterline within inches of her length overall, there was no doubt this 43-footer would go.

Kristofferson's main concern was to get the boat to lift evenly at speed. His big worry was the connectives. Hedley Nicol's flimsy amas had often peeled from the wings like perforated cardboard; the designer himself was lost at sea. Kristofferson designed bullet-proof connectives, tying two double-box beams and six other crossbeams directly into the ama bulkheads.

As soon as he saw that his 43-footer was going to work, Kristofferson drew the 31. Like her big sister, this was no sheet plywood boat. The main hull specifications called for two diagonal layers of 3/16-inch plywood planking over 1-by-2 yellow cedar stringers spaced 8-inches apart. Decks and underwings fit together like inverted saucers. Topsides and cabinroof were also wave-deflecting cambered curves.

Compromise crowded him in this smaller design. "After all," Kristofferson would later tell a packed Vancouver hall, "two people on a 31-footer need just as much food and gear as the crew of a 35-footer."

The only way to accomplish this - and still have a boat that sailed - was to keep the stern sections full and chop them off abruptly. There would be turbulence. But that stern would give the 31 many of her best qualities: load carrying ability, safety while surfing and a sure footedness that defies pitching in the roughest headseas.

Ama (“float”) design was even more critical. Cruising tris traditionally relied on big, full-buoyancy floats to keep them upright. But this didn't make sense to Kristofferson. Trimarans should sail on their main hull, he reasoned. The outriggers shouldn't dictate how the boat moves. The float had to be something that runs, something shaped faster than the main hull so that it wasn't dragging along pulling the boat off course.

He studied each section before drawing the outrigger as it must be: deep but narrow, asymmetrical to counter leeway and assist tracking, flat-bottomed to plane at speed.

He checked and rechecked his ama buoyancy calculations: 90 percent seemed perfect. Unique among cruising trimarans, "semi-submersible" amas would be the Kismet's best feature, allowing just enough "give" for the boat to heel to gusts, spilling wind and relieving rigging loads, even as they absorbed the sharp jolts of rough seas.

The shape looked fine enough to slice through wavetops. To prevent nosediving, Kristofferson extended the rocker so far forward the float bows ended up even with the main hull bow.

When he put his pencil down, everything seemed to work together in a craft that looked like she belonged on the water. Here was a boat that said, "I'll take you somewhere." Here was a craft that sang.

Though the Kismet 43 was the first multihull to appear in Sea magazine, her size was extravagant. People dropping by the shop to watch the big trimaran under construction saw the lines drawings for the 31 on the wall and began demanding plans.

At that time, 3/16-inch plywood - good both sides, better than anything available today - was selling for $4 a sheet. Gary Gagne and Harold Aune assembled their Kismet 31 hulls between the hulls of the 43-footer. Mark Gumley, just out of high school, built his boat in a lean-to alongside the shed; another 31 was constructed in back. Though still in diapers, Kristofferson's kids earned a fortune in pennies prospecting nails dropped in the dirt.

Suddenly there were seven Kismets under construction at Powell River. "For a while," Kristofferson recalls, "it seemed like there was a launching every other week."

But the week following Star of Kismet's launching was a nightmare. Kristofferson was sure he'd blown it. Onboard the big 43-footer there was no discernible motion; the sailor who hated to be passed couldn't seem to get his new boat to go. Then he noticed the chase boat growing smaller and smaller.

Speed without fuss became a Kismet trademark. By the mid-1970s there were 26 Kismets under construction in isolated coves up and down the B.C. coast. There was no network, no construction manual. First-time builders ranged from the inexperienced to the inept. But some of the hardest smitten by Kristofferson's demonstration rides had recently launched classic cutters and two-masters.

With their spacious after-cabins, visitors found it impossible to guess the length of the 31's. No Kismet carried an inboard engine - not even the 43, which dispensed with searails on the stove, as well. Though each boat was different, all shared a raised dinette surrounded by large windows - not ports - through which the light and view were startling.

The Kismet 31 weighed in at a solid 4,300 pounds - nearly twice the displacement of the 31-foot racers Dick Newick would later design. Even so, these funkier 31s were often heavily overbuilt, with big iron woodstoves and log-cabin interiors. Not recommended for offshore work, where weight is critical to safety and performance - but ideal for poking around a rugged north coast even Chileans say resembles Patagonia.

"Bushboats," somebody dubbed them. You could load one of these three-hulled jeeps to the gunnels with tools, beans, coffee and herbs and vanish for months at a time, bouncing off rocks and the occasional floating logs that hide in these waters like mines.

Even built to specs, the 31 is hell-for-stout. She doesn't like square chop - no multihull does. But offshore that buoyant center hull lifts like a balloon over heavy seas. You stay dry, on deck and below, and meals were civilized - even in a blow.

Dolphins greet us approaching the San Bernadino Strait, Phillipines

The secrets to sailing this stubby, shallow-draft hull are flat-cut sails and "lazy sheets" on the headsail - a 19-foot beam offers myriad sheeting angles. If you pay attention to sail trim - and what sailor does not? - you were rewarded by a craft that averaged seven knots on passage, and occasionally hit 15.

Leeway can be shocking, depending on conditions. Pacing a monohull upwind can be an exercise in frustration as you slide inexorably off to leeward. (The answer is to align your Kismet's bow with the diverging angle and let her foot fast.)

But the mini-keel's propensity to side-slip proved a lifesaver offshore. No breaking sea ccould wallop a boat which danced away from the worst blows like a ju-jitsu master. Inshore, a 30-inch draft enabled us to enter sheltering rivers, anchor serenely over murderous coral or glide over reefs into uninhabited lagoons. We could also put Celerity on a beach for bottom work - a handy feature when cash and boatyards were scarce.

Already the legends were beginning. Gumley's dismasted 31'er was run down by a Coast Guard hovercraft during an Easter storm. The mangled Kismet stayed afloat; the hovercraft took a year to repair. Then Gagne set out in company with Kristofferson's 43-footer for Hawaii. Seven days out, Kristofferson was shocked to see a Fraser Valley egg carton floating on the water ahead.

Cloud was using her whisker pole and sculling oar to fly studding sails off the shrouds. For four consecutive days she averaged 181 miles noon to noon. They ran right over the back of a sleeping whale and into the North Pacific High. Kristofferson beat them handily to Hawaii. But he would never again take the little 31 for granted.

But the power of his own 43-footer was amazing. On their return passage the designer and his family encountered three major storms and a cyclonic depression that sounded like music from the Twilight Zone. "It was exciting," Ruth recalls. "With a big boat you don't have to slow down."

Bill says he didn't dare put out drogues - the fittings would have been ripped from the decks. "I've never gone so fast in a boat ever," he says. "We just sat there and cringed."

Even bucking 30 knot headwinds, Star of Kismet made day's runs of 209. 211 and 217 miles, sailing 2,300 miles to the Queen Charlotte Islands in 18 days. The Kristoffersons bought property in a cove, building a house on one point and a boatshed on the other. Their oldest daughter was nine when they moved ashore for the first time.

The kids lived in rooms with 16-foot ceilings so they could play basketball indoors. It rains a lot in the Charlottes. It also gets windy. Between 100 knot winter storms, Kristofferson worked at the 24 foot drafting table above the sauna.

After designing several fishing boats and houseboats. he drew the Kismet 39 for a client who demanded a boat that would be first home.

The 39-foot ULDB racer offered sitting headroom and two benches belowdecks. Why a monohull? Kristofferson recounts "many nice sails" aboard outriggerless craft; half his sea time has been spent aboard them.

"You can do more aesthetically with monohulls than you can with tris," he admits.

But trimarans remain his first love. "A monohull with 50% ballast," says the free-swinging Swede, "is half-sunk before it leaves the dock.”

In 1974, Kristofferson designed Elora. The 34-footer seemed an ideal size: cheaper to build and maintain than her big sister, while boasting "walk-through" passageways instead of the "duck under" boxbeams in the 31.

But so many British Columbians who yearned to sail this spectacular coast could not even afford a 31. Instead, they built driftwood boats on island beaches, converted lifeboats, and sailed wrecks. What was needed, Kristofferson realized, was a cheap family beachcomber; something you could drag ashore, dismantle and stick in the garage.

Originally conceived as a utility boat, the Kismet 24 began as an outboard-powered surf dory. But clambering over crab pots and dead deer didn't appeal. And Ruth refused to go to sea off the Charlottes aboard a powerboat. "What happens if the motor quits?" she demanded.

So Bill penciled in a Hobie rig and demountable outriggers. What was this? Pull four bolts and you had a daysailing catamaran and trailerable camper. Put it back together and here was a trimaran weekender that drew eight-inches, weighed 1,100 pounds and carried the same sail area as the 31.

Speed and simplicity joined hands and danced around Kristofferson's drawing board. Flat surfaces were the key. There were no bilges - the cabin sole was the hull; each float bottom was as wide as a waterski. Deep, canted daggerboards would help pick the boat up onto the plane.

Kristofferson felt 17 again. Using quarter-inch plywood - half-inch for the bottom of the center hull - he built all three hulls flat on the ground in a day. The next day he spent trimming and glassing them. Kristle and Kenetta helped him paint. The entire project took three weeks and cost $5,100.

Like that Arabian dhow, the smallest Kismet didn't seem to have a limiting hull speed. Regardless of the sailing angle, in 15 knots of breeze, the 24-footer skied onto the step. Her designer was just starting to enjoy the ride when a real ripsnorter folded the flukes on a 40-pound Danforth and Eclipse dragged ashore. She was a total loss.

There were other disasters. Though no lives were lost, the capsize of CloudWindspeed and (tripped when held beam-on to heavily breaking seas by a parachute sea-anchor) in hurricane seas off New Zealand and the northern B.C. coast proved that lying ahull in survival conditions invites disaster.

Only after several gales at sea and a force 12 blow that curled my toes, did I understand that a good cruising trimaran is the ultimate seaboat, at her best when buoyantly riding out heavy weather - preferably tethered to a parachute sea-anchor.

If seamanship is essential to multihull safety, the advent of lighter, stiffer boats carrying more efficient rigs is redefining the performance cruiser. Kristofferson does not believe that it's somehow more "traditional" to lumber along at four knots getting clobbered by every depression and freak storm spawned by an increasingly erratic Greenhouse climate.

"If you want to spend time at sea, why spend it in the middle?" he asks. "Why not go to an island and sail around it for a few days?"

What about two hulls? According to Kristofferson, only at 45 feet does a catamaran offer a performance advantage over a trimaran. The Kismet 45 is a cat.

But in his Kismet 40 trimaran, Kristofferson has again broken with multihull tradition by choosing a rotating 3/4 rig.

On a cruising boat?

"A three-stayed, three-quarter rig has 36% of the compression loads of a conventional masthead rig," the designer states. "The full-battens automatically tension the mainsail. As the wind increases, you can rotate it, depowering the sail."

Both the new Kismet 31 and the 40 deploy "helper" foils - canted float daggerboards which lift the outriggers, cutting drag while the main hull rides flat as a surfboard. "It's a little rougher riding," Kristofferson concedes. "But of course it's your option . You can always pull the boards up."

He insists that his boats be built of wood, "It's very hard to build a light foam-sandwich boat. And with 'glass you can't change anything. You can't even add a cleat."

I remember all those indispensable changes made to Celerity over 15 years of treating her like a floating pegboard. Here's to plywood, I think: Lightweight, easy to work, incredibly strong and resilient - and a horror when it rots or delaminates. Still, 16 years and 42,000 sea miles is pretty good going for a plucky backyard boat…

Double-reefed at sunset, she charges the night at seven knots, phosphorescence streaming like contrails from three transoms. Lying snug in the big aft-cabin, with the wash roaring through the underwing tunnel less than a half-inch from her ear, Thea soars to the boat's tilt and rush as if cradled between the wings of some great seabird.

Gauging the jibs against the angle of the snapping ensign, I ease a few inches on yankee and stays'l trim. The response is immediate acceleration. Like any thoroughbred, Celerity sulks when over-reined. But start the sheets and she delights in riding "the groove."

It is immensely satisfying to work such a responsive creature. What greater tribute can be paid to any craft when, after two weeks of demanding sea routine, the off-watch comes up on deck, disconnects the autopilot, and hand-steers for hours for the sheer pleasure of guiding her across the open sea.

Photo Captions

Celerity sailing south, close-hauled far out at sea -Will "Randy" Thomas photo

Celerity approaches Victoria, BC closing the circle of her 8 year Pacific circumnavigation

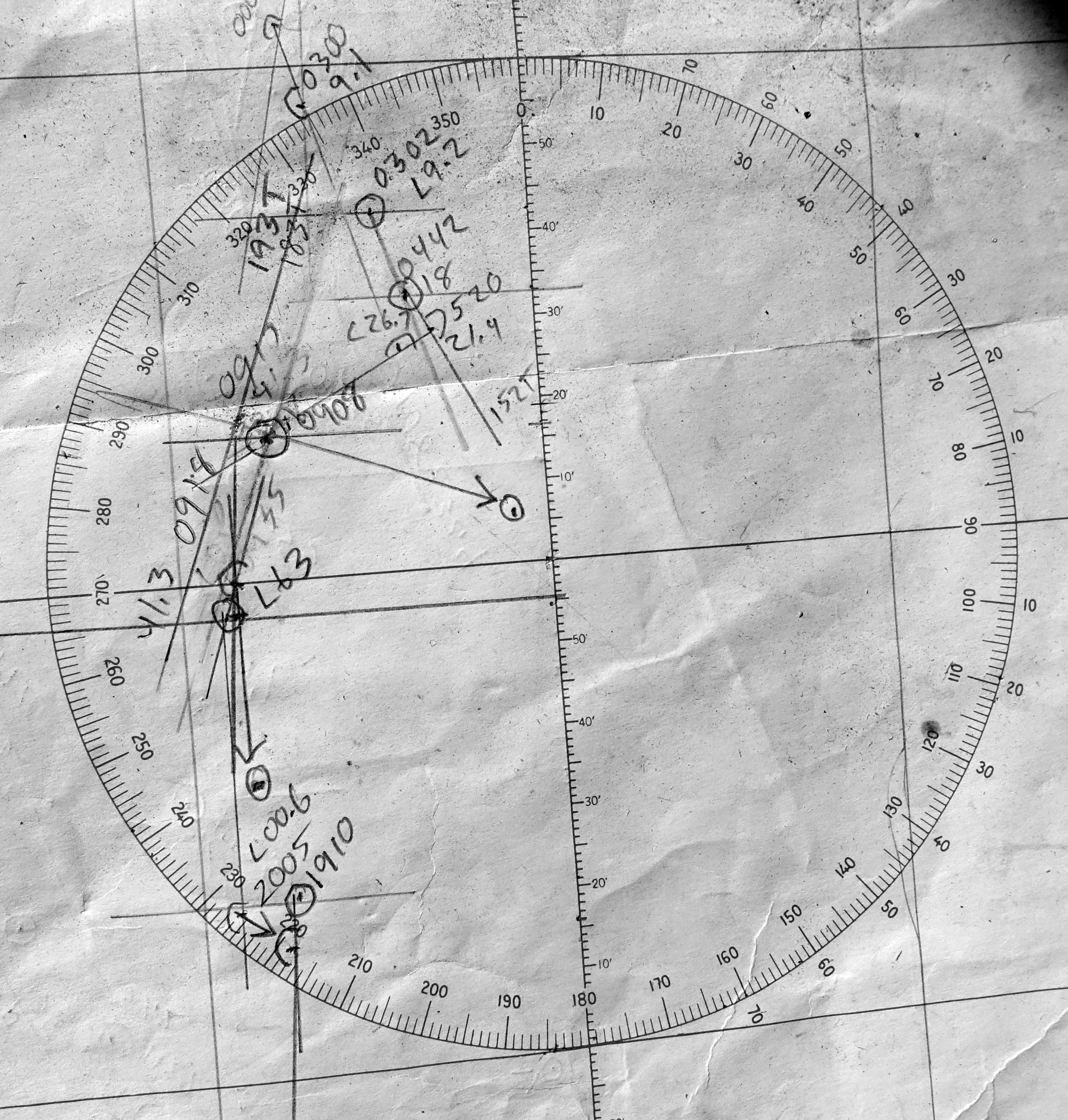

Plotting Sheet 42N 125.5E Sept 18 '78 southbound from Victoria to San Francisco -Will "Randy" Thomas photo

Tuckered Thomas 5 days out of Ponape -Thea Mortell photo

Dolphin shows the way into the San Bernardino Strait -Will "Randy" Thomas photo

Thea reefing the mainsail in a hard blow 100 miles off Oregon coast -Will "Randy" Thomas photo