SHIN AITOKU MARU

SHIN AITOKU MARU

by William Thomas

She’s small as ships go, only 1600 Dead Weight Tons. Patches of primer on the tanker’s low hull attest to four years’ hard service on an oil hungry coast. But it’s her towering steel-and-canvas sails that command attention.

They open with a hum of hydraulics – a chrysalis of unfolding framework locking into precise laminar curves on steel masts fore and aft. Sensors taste the state of the sea and air. A microprocessor compares wind and sail angles, then issues a command. Eerily, nearly silently, the twin foils rotate to face gusts sweeping off the scroll-like mountains of Honshu.

No breeze is felt on the air-conditioned bridge, where a video screen displays two parabolic sail symbols turning to trap shifting arrows of relative wind bent by the ship’s passage. As Shin Aitoku Maru takes the wind’s full thrust, a second computer cuts main engine revolutions and increases propeller pitch. Ship’s speed holds steady at 14 knots. But fuel consumption plummets from 4.1 to 3.6 tons of bunker oil per day.

$181,000 is an annual savings – and a revolution – that the Japanese Government and ship owners understand. For it is ships – thousands of oil-fired vessels maintaining a round-the-clock transfusion of petroleum, food and raw materials – which keep this far-flung island nation alive.

Just as the advent of steam and cheap fuel spelled the demise of commercial sail 150 years ago, new technology and the “oil shocku” of 1977 have hastened sail’s return. When N. Hamada, president of the Japan Marine Machinery Development Association (JAMDA) ordered his experts to investigate sail in 1978, he did not envisage resuscitated square-riggers answering his nation’s needs.

Even in the grip of a national emergency, with fuel prices doubling overnight, Hamada knew that the windjammer’s drawbacks of large crews, obstructed cargo handling and erratic schedules would be unacceptable to contemporary shipping firms motivated more by economics than nostalgia.

Full automation would be necessary to keep crew complements the same. Free-standing masts would not obscure cargo access. But the genius of Hamada and his staff lay in their decision to develop sail-assisted motor vessels, rather than resurrect the windjammer concept.

Breaking tacks with Western efforts to head offshore with large, auxiliary-powered sailing ships, the Japanese turned to reducing fuel consumption among their coastal fleet. Running main engines continually would ensure schedule reliability in predominantly fickle inshore breezes. But it was hoped that the addition of super-efficient sails would cut fuel consumption significantly.

Sail design was critical to success. With an engine-assured apparent wind coming from ahead, researchers at the giant Nippon Kokan Corp. sought a maximum-lift sail with low induced drag. Using computer and wind tunnel simulations to correlate North Pacific wind patterns with various sail configurations, they found the best shape to be a laminar-flow airfoil with a high aspect-ratio and curved leading edge. The resulting sail would be tall and lean rather than low and broad.

Daiho, a one-fifth-scale large cargo carrier, was quickly built by NKK to test these theories. Setting a variety of soft, rigid and triangular sails on three masts, the experimental ship explored the trade-off between sails that were inexpensive, high-performance and windward-biased. Despite its high cost, the distortion-free rigid foil won those trials handily.

Five years of development had been compressed into 24 months. Japan’s shipping magnates, however, balked at the uncertainties of building and operating a working prototype.

Stability was a major concern. Despite JAMA’s assurances, high winds and tophamper seemed a poor combination in waters lashed by up to a dozen typhoons every year. Reliability posed another risk. In the charter game, shipowners forfeit the fees paid by operators for the time a ship lay idly out-of-business – or is “off-fired” in the trade jargon. Mechanical breakdown, indeed any condition deemed unsafe by the operator, can result in cold boilers. And no pay.

Charter rates are based mostly on the current market price of oil. Fees fluctuate monthly, with savings split equally between the owner and operator. Sails might give a shipowner a competitive edge, especially if oil prices rise.

Aitoku Company, a modest, Tokyo-based firm which owned five coasters in the round-Japan trade, was working with the Japan Marine Engineering Company to improve fuel economy by preheating bunker C with engine exhaust, instead of the usual electric heater. When JAMA asked Aitoku to consider sails, the company agreed to commission the world’s first sail-assisted tanker.

“We hope,” the pioneers said, “to pave the way to general use of commercial sail.” They also hoped they wouldn’t lose their shirts.

Shin (“New”) Aitoku Maru was delivered by the Imamaura shipyard in September 1980. Designed from the keep up to incorporate the latest developments in sail, the 66-meter ship is four meters longer than her conventional sisters, She is also a half-meter narrower. Draft was increased only slightly, from 5 to 5.2 meters. But the size of her bilge keel was doubled and the rudder area increased by 150%.

None of these modifications are visible from the bridge. What dominates the view ahead are the sails: two vast rectangular shapes, each nearly 200 square-meters in area, rotating like sentient antenna seeking the subtlest nuance of breeze.

No yards, booms or rigging are visible. The pipe-laced deck is deserted. If the ship was not moored firmly to the Kawasaki refinery pier, one could imagine this craft hurtling not through seas, but space.

Strapping a construction worker’s helmet to his close-cropped head, Captain Atsuo Shimamoto checks the loading console as Shin Aitoku Maru settles deeper on her marks. A master for 22 years, Captain Shimamoto has never felt the pull of a mainsheet or heard a sail flog. But the pride of sail is in his voice when he speaks of his ship’s “style”.

“My ship is an all-weather ship,” he says through an Aitoku interpreter. “My ship handles better than a 2,000 tonner. She is better in typhoons.”

He pauses, as if hearing the anxious mutterings of his crew during those early voyages. “We are seamen – not sailors,” they had complained. The sight of all that windage conjured visions of capsize.

Captain Shimamoto recalls their first typhoon: 60 ships huddled in the lee of Sado Island as storm-force winds screamed through Nigata Port on Honshu’s northwest coast. Though heavy breakers reduced the navigable entrance to. 30 meters, the 11-meter-wide Shin Aitoku Maru threaded the S-shaped channel with an aplomb any shellback would have admired. She was the only ship to enter port that day.

More blows followed. In April 1981, a 50-knot frolic off Shikoku. In June, en route to Taiwan, a real rip-snorter – eight-meter seas and gusts to 64 knots. The hybrid sailing tanker was four-hours late.

“My crew has confidence,” their captain declares today. As their ship kept the seas – and her schedules – in conditions that forced her competitors to seek refuge, it became clear that sails actually improved merchant ship stability.

Even when folded to half-size in Force 12 winds, the sails resulted in heeling of no more than five-degrees. Pitch and roll were so effectively dampened that the tanker’s generator remained coupled to main shaft – an inconceivable gambit in conventional ships, which race their screws when plunging into headseas.

Taking pencil and paper, Shin Aitoku Maru’s master sketches his ship with the wind abeam and slightly abaft her beam. “This is her best sailing angle,” he explains. Though course is never altered to accommodate shifting winds, the tanker tacks though 60 degrees, making efficient use of wind as close as 30 degrees to the bow.

The ship logs 50,000 nautical miles each year working the coasts of Honshu. Using sails 60% of the time, the gleaming black-hulled ship has averaged 20% fuel savings and a 1.4 knot increase in average speed.

The sail-assisted ship is almost breaking even. Even with fuel prices temporarily stabilized in the wake of the Gulf Was, the costs of amortizing and maintaining her sailing gear exceed her fuel savings by only $8,200 per year.

With the Americans abandoning their own commercial sail plans, and conventional West German studies predicting double the costs of the Japanese approach, Aitoku ordered two more sail-assisted ships – a 3,200 DWT tanker and an LPG carrier for deliveries to Taiwan and mainland China.

Unlike their predecessor, these are single-masted ships. For Shin Aitoku Maru demonstrated that even on merchant ships, a single large sail reduces costs and complexity, and is just as efficient as two smaller sails, which interfere with each other on dead-downwind courses.

As insurers lowered their premiums for the safer, more stable sail-assisted ships, Aitoku’s rivals rushed to retrofit their fleets.

But none of their add-ons met the new SOLAS regulations concerning safety, stability and construction drafted by the Transport Ministry for sail-assisted ships. It was cheaper to build from scratch.

By the late 1980s, eight modern sail-assisted ships were operating in Japan’s home waters. Latest additions include a passenger ferry making scheduled runs out of Nagoya, and a 5000 DWT tanker launched in Shikoku.

Visualize three Shin Aitoku Marus bolted together and you can sense the latest single-master’s imposing size. Multiply the original sail-assisted ship sixteen-times and you have the shape of ships to come. This leap in size is as inevitable as the offshore routes that followed. The short-haul coastal trade has always been notoriously inefficient under sail. Adverse tides, contrary winds, constant docking and undocking rarely allow a sailing vessel to hit her stride. If Shin Aitoku Maru could occasionally achieve a 25% fuel savings, despite these handicaps, what might be expected of much bigger sisters sailing trans-oceanic routes?

JAMDA computers predicted an incredible 50% fuel reduction for 10,000 to 35,000 DWT sail-assisted ships on the long North Pacific crossing.

The costs of such hybrid ships were not made public.

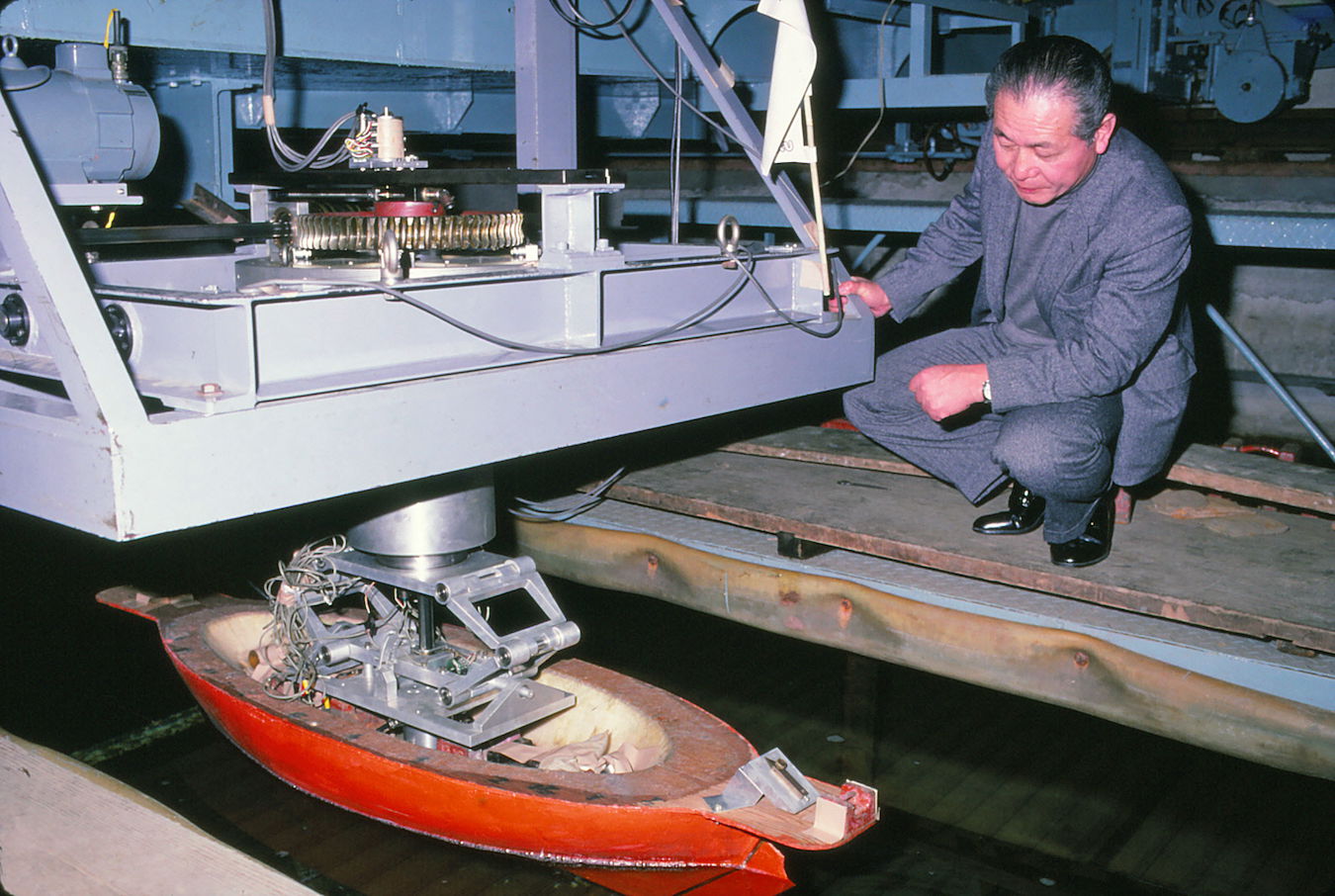

JAMDA officials were already looking for high-rolling backers when the co-designed of Shin Aitoku Maru paused outside his towing tank at Osaka University. “Fifty-percent fuel savings are considerable,” Dr. K. Nomoto remarked. “But the cost of sails and computers for a ship this size is staggering.” He paused, a dapper man in a turtleneck and slacks trying to weigh the odds of such a venture.

“Right now, the balance point is just critical,” he concluded. “The boundary between profit and loss is very fine.” Which might explain why construction of Japan’s biggest commercial sail entry – a mammoth 26,000 ton oceangoing bulk carrier – remained as shrouded in secrecy as an America’s Cup 12-meter racer.

JAMDA’s sponsor – a consortia still unnamed – dispensed with a three-mast configuration in favor of a single, sky-breaking spar stepped on the ship’s forward deck. This lone rigid sail must propel this fantastic motorsailer to cost effectiveness at an average speed of 15 knots.

The new sailing bulk carrier now serves the Tokyo-Vancouver, Canada run. As other trans-Pacific freighters follow, the ghosts of the last tea clippers to depart Far Eastern shores must view their progeny with wonder. And once again, nations will trade under sail in the decade before the Millenium.

Photo Captions:

Shin Aitoku Maru taking on oil at Kawasaki refinery -Will Thomas photo

Captain Atsuo Shimamoto with company interpreter -Will Thomas photo

N Hamada at Osaka U. towing tank -Will Thomas photo