INTO THE STREAM

INTO THE STREAM

by William Thomas

(with Ernest Hemingway)

No matter what how many double daiquiris he’d downed watching CNN the night before, there was no escaping the rising sun. Coming up in the Florida Keys it wakes you every time.

The sky was clearer than his head when Ernest Hemingway left his antique desk at 907 Whitehead Street. Making his way to the main house across a swaying rope bridge that kept all but the most foolhardy visitors at bay, he asked the black servant Louis to make him a breakfast of cold beer, corned beef hash and eggs. Ignoring the complaints of his extra-toed cats, the author ate quickly and went out into the shady relief of tree-lined streets, still blessedly quiet at this hour.

Just after daybreak in early July, it was already hot. “The trouble is that Key West is on the same latitude as Mecca,” a boating writer named Michael Palin once observed. For some reason Hemingway never completely understood, his second wife Pauline had replaced all the ceiling fans in the house with chandeliers.

He was tempted to take a detour and belt back a few quick ones at Sloppy Joe’s. While Pauline had stayed home with Bumby, he’d met Martha, the woman who became his third wife, at that former speakeasy before they’d gone to Spain together to cover the civil war. But there wasn’t time. His guests would already be converging on the boat.

He still missed Gregorio. Born under sail in Lanzarote in the Canaries, Gregorio Fuentes had lived past a hundred. But now his beloved boatman was gone. Clarence Freiloux had taken his place. The no longer employed shrimp boat deckhand from southern Louisiana greeted Hemingway as he stepped aboard.

The famous writer immediately felt better. He always did onboard Pilar. That joy had never waned since he’d commissioned the 38-foot cabin cruiser from Wheeler Shipyards in New York in 1934. A wooden vessel, built by hand, she was a big black boat with green topsides and decks that are easier on the eyes than glaring white paint in the tropical sun.

With her low-slung stern and that big roller spanning the transom to bring the swordfish in and a five-hundred mile range, Pilar had legs and an easy motion in any kind of sea. Always an innovator, Hemingway had been quick to adopt oversize outriggers capable of dragging 10-pound baitfish through a summer seaway. He also added the flying bridge with dual controls atop the veranda-like cabinroof that identifies Caribbean fishing craft.

“She’s gassed up skipper,” Freiloux reported. Water tanks are full. Ice and provisions are stowed. Weather’s calling for light sou’westerlies.”

Hemingway grimaced. “Onshore. Just what we don’t need.”

“I figure it’ll back nor’east by tonight. Gonna be hot though. Real hot on the water,” Freiloux said,

At least we won’t be wiping up puke, Hemingway thought. Or driving the bows under. When the Gulf breeze gets up out of the nor’east and blows against the current, it makes up a big sea. Judge it wrong — make a hard turn without picking your chance — and one of those breaking crests will roar down in on you with a thousand tons of seawater. And you won’t be going out into the Stream any more.

“Both our guests here?”

Freiloux tipped his head toward the companionway. “I put them in the cabin till we get underway.”

Hemmingway nodded. “Good. Single up the lines and prepare to cast off.”

The reek of petroleum was so strong he ran the blowers an extra two minutes before firing up both gasoline engines. As the familiar vibrations came up through his feet, Hemingway realized that the cloying stench wasn’t coming from the boat. The papers were saying that people started experiencing physical symptoms when the hydrogen sulfide coming off the oil slicks reached 5 to 10 parts per billion. Last Thursday, the EPA had measured levels at 1,192 ppb in Pensacola. Benzene was much more toxic. But the news wasn’t mentioning benzene much. Freiloux let go the crossed springlines and turned his eyes to the skipper. Mounting the ladder to the fly bridge with an alacrity he knew would cost him later, Hemingway tested the controls and nodded again.

The boatman let the bow and stern lines run through the dock cleats as Hemingway backed out. Even this early in the day, the channel was always choked with boats of every size and class heading out to the rich fishing grounds over the DeSoto Canyon. Here, close off the Florida Panhandle, nutrient rich upwellings from the deeps nourished the vital coral nurseries in shallower waters where mollusks and other fish fed.

This early, there were only a few small craft underway. None was rigged for fishing.

“Thank our guests and give them the run of the decks,” Hemingway instructed Freiloux. “And tell them one hand for the ship or they will have to deal with me.”

“Right skipper.”

Freiloux ducked below.

The woman scientist was the first to gain the deck. Hemingway eyed her as he might appraise the lines of a newly introduced seacraft. She’s young, he thought. But then, at his age all pretty women seemed young. Or all young women seemed pretty. She wore decent deck shoes and a downeaster cap and appeared at ease on the water. He approved of her at once.

Holding the big brim with one hand, she looked up. “Permission to come up to the bridge.” Hemingway put the wheel over two spokes to pass a can buoy close off their starboard side. “Sure,” he called down, straightening the helm and adding a few more rpms for the run out to sea. “Samantha Huntington,” the newcomer said, offering her hand. The boat swayed as the heavy hull tasted open water. But she was already backed securely against the rail, her grip as firm as any man’s. “NOAA. Maybe ex-NOAA after this,” the ocean scientist added with a rueful grin. “Thank you for bringing me along. Washington’s only paying to send out people who will report what the administration wants them to report.” “Glad to help,” Hemingway said. “It isn’t right trying to cover this up.”

Her eyes flashed. “I thought you rarely took women onboard.”

Hemingway gazed into a distance she could not begin to imagine. “Dying changes a man.”

* * *

Pilar was fast for the fish and very able in a seaway. With no wind to oppose the tide and the ebb pushing the Stream away from the mouth of the harbour, he headed her out over the bar and ran straight out to where they could see the dark line of the Gulf. Out there, where the turquoise shallows grow dark, the sea turned so blue it seemed to bleed that color from the sky.

Once again, Pilar was on patrol. This time they weren’t hunting the U-boats that had sunk hundreds of tankers in the Gulf shortly after the United States entered the Second World War. The Germans often stopped native fishermen to trade or confiscate their catch and fresh provisions. Hemingway's suicidal plan had been to use Pilar as a Q-ship to seduce a U-boat into laying alongside. Then they would open up with Tommy guns on the sub’s deck crew and try to toss grenades down an open hatch.

Fortunately for everyone, the only U-boat they sighted didn’t bite. On bait her captain ignored. Happily for Hemingway, he accidentally shot himself in both legs with his Colt .22 instead of the burp gun.

He smiled remembering how he’d tried to shoot that shark when the gaff broke and the gun went off. Didn’t even hurt. It wasn’t like getting shot in Spain and the doc had wisely left the bullet in his leg. But this new quarry was different. How could so much crude oil be a worthy opponent when everyone knew it was going to win.

He’d rather be fishing out in that great deep blue river, three-quarters of a mile deep and seventy to eighty miles across. This light southerly breeze would stop all the fish biting off the north coast of Cuba. But it would make them bite off the keys. He resisted the urge to change course and go down to the fighting chair. Ignoring a sore butt and back, left hand curled around a cold bottle of Hatuey beer, the right gripping the reel, he would watch the bait bounce and both teasers dip and dive and zig in and out of the wake…

“Feesh! Feesh, Papa Feesh!”

Gregorio stamping his feet up and down, the signal for fish. His last wife, Mary calling from the top of the deckhouse, “Isn’t he beautiful? Oh, Papa, look at this stripes and the color of his wings. Look at him!”

There must be a good reason for that big sail. What is it?

When you see him raise his dorsal fin and spread those wide bright-blue pectorals like some great undersea bird and the slicing wake of that fin cuts toward the bait, you know he is going to strike. Out of hunger, anger, indifference or sheer playfulness, he is coming in.

Squid is the marlin’s favorite food. Fuentes flicks the dancing two-foot wooden teaser ahead of the billfish, leading him to the feather lure. He’s going to take it!

You just have time to jam the rod in its socket as that shadow comes in, fast as the shadow of a plane moving over the water. You hear the pin click as the line pulls clear of the outrigger. The butt slams you in the belly. The line springs taut as a banjo string. Little drops come from it as you pull back hard and feel his weight.

“Oh God, the bread of my children!” The overjoyed boatman screams this over and over again.

You quickly loosen the new VomHofe drag as the great iridescent fish jumps clear, throwing water like a speedboat. Forget the sun beating down on your head. Ignore the straps of the fighting harness digging into shoulders that will soon be screaming in pain. The really huge fish always head out to the northwest when they make their first run.

Just get your own boat turned after him as he heads out to sea. That will be up to Mary. Short curly blond hair tousled by her effort and the breeze, she has to back Pilar fast and turn, gunning both motors to follow the heavy white line slanting steeply into the deep blue stream. You are concentrated on staying connected to a creature strong as a wild horse. Your task is to tame him, break him and convince him to come in. The friction of the line in the water will eventually tire any fish. Or snap.

The biggest fish he ever caught was a 542 pound blue marlin in 1935. It measured nearly 13 feet long. Eight times it jumped completely clear of the water. Each jump the hook cut the hole a little bigger in his jaw…

* * *

“… share?” Samantha Huntington’s smile invited revelations.

“Oh, just remembering the fishing out here.” Hemingway reflexively scanned the weather horizon. “Fighting a big marlin for one or three hours is better than bull fighting or hunting big game.”

He stopped, embarrassed. He sounded like an old man trying to impress a handsome younger woman with ancient yarns. Most times the swordfish got away anyway. If you took longer than an hour to boat them, the sharks moved in, leaving you just the head and bill. The big commercial boats had been worse than the hammerheads.

The scientist seemed intrigued. “I would think that hunting across the African veldt would be an even wilder experience,” she said.

“Not any more,” Hemingway said. “Not unless you count being shot by poachers in one of those tame game parks a wilderness adventure. In the first place the Gulf Stream and the other great ocean currents are the last wild country there is left. Once you are out of sight of land and of the other boats you are more alone than you can ever be hunting and the sea is the same as it has been since before men ever went out on it in boats.”

“And women too,” Huntington gently chided.

“Women, too,” Hemingway agreed. He thought of Mary Welsh and how she listened to him like none of his other wives had and how she looked like the actress Mary Martin when she handled the boat.

Once his war bride had stopped engines and a great black fish had towed the boat stern first. The long-billed fish had sounded four times. Each time he went deeper. When there was no line left on the 400-yard spool, Hemingway had hung over the side with the rod underwater, bent double with all that weight pulling down, down, down. He put all the drag he dared on that premium $250 reel before he finally turned the fish and brought him to the gaff.

“Back then, the Gulf Stream was an unexploited country,” he chose to say instead. “Texas, Louisiana and Oklahoma were forested with oil rigs. It seemed the oil would never run out. Or that we would ever need to take if from under the sea. No one ever guessed the swordfish would run out either. In 1933, from the middle of March to June, 11,000 small marlin and 150 large marlin were brought into the Havana market. Any July and August it was even money any day you went out you would hook into a 300 pound fish or bigger. Figure on ten cents a pound delivered to the dock. When the man who carried your fish to the market came back to the boat with a long roll of heavy silver dollars wrapped in a newspaper, it was very satisfactory money. It really felt like money.”

Now the woman was appraising him.

“Of course, you still had to get up every morning at daybreak,” he went on. “Gas in Havana cost 30 cents a gallon and you had to sleep on your belly most nights because of what the fish did to your back. And the ocean could swallow you as casually as a rusty seacock giving way or a rogue sea suddenly overwhelming even the most well found craft. But each fish was so wonderful and strange. And who knew how old he was?”

“That’s from The Old Man And The Sea,” Samantha Huntington said. Her eyes shared his love for what was still a fine Stream.

How could he tell her that putting the shotgun in this mouth and pulling the trigger like his father had done had finally cured him of killing? And what did that lesson matter when the Gulf Stream was carrying its own demise toward the Florida coast at a steady five miles every hour.

Hemingway’s gaze left hers to check the sea astern. The man who had also asked to join them was standing in the back of the boat looking down into water so calm he could glimpse bottom at 30 fathoms. Dark streaks of purple obscured his view. They did not portend plankton or deeper water, but something alien, creeping and insidious. The stranger frowned.

Ernest Hemingway wore the same expression. He was usually happy this far out. When the other boats were gone and he looked astern and saw that no land was visible he relaxed. Today the ocean was empty.

But he could not relax.

The sun would be frying them soon. He would have preferred to run eastward with the current in the morning, headed into the glare, before returning against the current with the sun at its hottest at their backs. But the threat they wanted to intercept lay to the west. He nudged the throttles up.

Over the steady bass thrum of the motors, Hemingway and Huntington watched the small whirlpools demarking the edge of the Stream. Usually the sign of a fast-running current, they seemed sluggish now, clogged by a rainbow sheen. The reek of benzene, toluene and xylenes was pungent on the breeze.

The papers said that if you could smell oil or see an oily mist drifting down that meant the benzene level was already hazardous to human health. But the real disaster stretched mostly unseen from just beneath the surface down to about 3,300 feet. At 1,300 feet, rivers of crude spewing from the wreck of the Deepwater Horizon was already painting bright Lophelia corals with poisons that would dim their colors like fading lights, finishing off what warming waters had already started.

Moving with authority into the low swell, Pilar ran for an hour before overhauling a big patch of yellow gulf weed. Looking down from the flybridge, we could see a bird on it. It was dead. As Hemingway backed down to swing them alongside, Huntington climbed down to collect the specimen.

“Goddamn dispersants.” Their male supernumerary had replaced the scientist on the bridge.

“Dispersants break up the surface slick and make the nightly news look better for BP,” I said. “But Corexit sinks the oil where it can’t be collected and makes it much gooier and oilier so it doesn’t degrade very easy. It’s a different world a mile down. Freezing cold and dark, like a fridge with the door slammed shut. The high pressure at those depths makes it hard for bacteria and dispersants to break up the oil.”

Hemingway kept his eyes on Samantha Huntington. The scientist leaned outboard and deftly snagged the dead tern with a scoop net. Looking up, she met his eyes. Hemingway put the engines back in gear. Then he turned to me.

“Tom Guidry,” I said. “Appreciate the lift. Though right now I’m not sure I want to see this up close.”

“Even if you stayed ashore, you will be seeing plenty soon enough,” Hemingway said.

“That’s true,” I said.

“You know your way around the water.”

“Been running my own shrimp boat since I was 14,” I said. “My daddy taught me. Got into guiding rich sportsmen for a while. Then like a lot of shrimpers I went to work for some of the oil and gas outfits. Brown and Root, Amaco, Hess, BP. Hell, I don't know anyone who don't work in seafood or oil and gas."

“With the bayou resorts as empty as the traplines, I guess that’s all gone now. The fishing,” Hemingway said. I heard anger mixed with grief in his voice. Just like that woman’s eyes when she snagged that bird.

“Oil extraction is a filthy business,” I agreed.

“Yes, well, it’s running Pilar. And it has to come from somewhere.” Hemingway sounded resigned.

"It's bad what's happening, but we still need the oil to survive," I said. “People from the bayous, it's their livelihood. It's what they've always done is work offshore on a drilling rig. I would hate to see drilling be stopped in the Gulf because of families losing their jobs just like the shrimpers are. All them small wheels keep the big wheels turning.”

Huntington came up the ladder one-handed. Both men examined the corpse she held out to them. The bird’s head flopped as she gently turned it over.

“It doesn’t appear to be oiled,” Hemingway said.

“A lot of the creatures dying out here aren’t,” the NOAA scientist said. “Corexit kills sea life, including seabirds and marsh-dwelling invertebrates. And BP has dumped more than a million gallons of that shit out here.”

“Is ‘shit’ a scientific word?” Hemingway asked.

“It is what it is,” Huntington said. “This… crap damages the liver and reproductive organs. We’ve already got dolphins dying from internal bleeding. And dead turtles are washing ashore with no visible signs of oil. The Gulf is one big flyway, as you know. We’ve got more than a hundred species of migratory songbirds and three-quarters of all migratory waterfowl in the U.S. flying through here. If they come into contact with dispersant they won’t be able to reproduce. Even after they've been rescued, cleaned and released from a facility in Tampa, the birds with the strongest homing instinct — especially females looking for their nests — are flying back into the oil.

“Goddammit,” I said, thinking BP and hoping He would.

“This isn’t a ‘spill’,” she continued. “Two months into this and we’ve still got a million gallons of crude gushing from BP’s underwater volcano every 24 hours. With commercial fisheries failures declared in Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama, you can say sayonara to half of America’s oysters and shrimp. More than a third of its blue crab and a quarter of its fin fish are on their way out, too.”

Hemingway and I said nothing. The closures were all over the news.

“The Alaskan fisheries have yet to fully recover from the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill. Some species of fish never returned,” she went on in a voice so low I had to cock my head to hear. “As much as a Valdez-worth of oil may be entering the Gulf coastal waters every four days.”

“Government doesn’t want to go there. No one wants to be reminded of the costs of our oil addiction,” I said. “We’re going to be decade dealing with this latest mess. That is, if we are incredibly lucky. Unless everyone starts riding bicycles, it will probably happen again.”

Hemingway and Huntington traded glances.

We’re all complicit, Samantha Huntington thought. It wasn’t just that the ‘non-negotiable’ American way of consumption is completely dependent on oil. It was that we waste so much of it. And then throw it all into the sky where it traps the heat of the sun.

She knew she was pushing both men toward angry denial. But her own grief and outrage wouldn’t let her stop.

“Don’t think this disaster stops with a few closed fishing resorts and higher fish prices. The zooplankton and other small organisms that anchor the entire marine food web and provide most of the oxygen we’re breathing right now are taking in toxins that will concentrate as they move up the food chain. Ingested oil damages the internal organs and immune systems of animals and can cause behavioral changes that impact their survival.”

She was starting to rant. She didn’t care. Try saying this at the office and her coworkers would begin to mutter and back away. Out here there was no place for her audience to go.

“Who knows when they’ll ever get this blowout capped. Boring the relief well means intercepting a five-foot diameter drill casing where it ends, about 18,000 feet underground.”

Hemingway shook his head. “It better work,” I said.

“It better,” she agreed. “Deepwater Horizon tapped into a deep fault of hydrocarbons maybe as big as the Ghawar field that’s been going for 70 years in Saudi Arabia. No matter how good the jury-rigged seal, that busted wellhead could keep seeping for decades. It’s going to spread to the Atlantic coast up through North Carolina. Fishermen in Prince Edward Island, Canada are worried because the Bluefin tuna they catch off their shores are born right here.

“But it won’t end there. The Gulf Stream will carry it to Iceland and the North Sea. What happens if all this oil and chemical dispersants change the character of the Gulf Stream? It’s already starting to slow because of all the cold fresh meltwater flowing off the melting icesheets. If this big spill changes the path or velocity of that ocean conveyor, we’re going to see some really hard weather. And a lot more creatures are going to die.”

“Isn’t that a little doomsday?” I said.

“She could be right,” Hemingway said. “Ships still pump oil over the side to calm rough seas. Dump enough of it into the Stream and… ” he stopped. Everyone looked stricken.

“We won’t know till we know,” Huntington said. “Right here in the Gulf we’re looking at the potential devastation of 8,300 species, including endangered Kemp's Ridley sea turtles, Brown pelicans, Atlantic Bluefin tuna, Mexico sperm whales. And there’s something else happening out here.”

She looked at both of us.

“I think many of these animals are being asphyxiated.”

“Methane,” I guessed. “Deepwater Horizon was drilling in an area known as the Mississippi Canyon. I’ve got a government chart showing methane hydrate-bearing sediments all through that area. Hell, the Deepwater rig was blown up by a methane bubble. And the live video feed from BP’s underwater camera is still showing methane bubbling up from the seafloor.”

Huntington gripped the metal grabrail as Pilar curtsied to a passing swell.

“You’re right,” she said. “Each cubic meter of frozen methane hydrate is equivalent to over 160 cubic meters of methane. It expands as it rises, growing from the equivalent of a six-foot bubble to the height of the Eiffel Tower by the time it reaches the surface. Since the Deepwater rig blew, we’ve never seen concentrations of methane this high in this Gulf. One plume we were able to trace underwater is three miles wide and 600 feet thick and contains levels of methane gas 10,000 times greater than normal.”

“And methane displaces oxygen,” Hemingway said.

“Depleting oxygen levels under the water and creating massive dead zones that kill plankton and everything above them that’s moving too slow to get out of the way,” I finished. Addressing the scientist, I asked, “How much methane are we talking about?”

Samantha Huntington looked away. Like a medical doctor cornered outside an emergency room, she could not duck the question she most wanted to avoid. Turning back to face us, she said, “Infrared satellite imaging shows that Deepwater Horizon drilled into a methane cavern approximately the size of Mount Everest. The gas bubbling up from that broken pipe is gradually weakening its ceiling.”

I felt myself turn pale. Hemingway was so startled he pulled both throttles back. The sudden hush of the motors accentuated the silence. Like dance partners on a tilting ballroom floor, everyone shifted their stance as the drifting boat started to weathercock beam-on to the low southwest swell.

“How much time do we have?” I finally asked. “I want to know and I don’t want to know.”

“We don’t know,” Samantha Huntington said as Hemingway came in with enough power to turn the boat stern-to-sea. “It’s a race to plug the pipe before the whole cavern collapses. If the seafloor slips, if there’s a landslide, the resulting gusher will spew out crude and methane… ”

“Until…” Hemingway prompted.

“Until the cavern is emptied.”

I groaned. “Then we’ll really be screwed.”

The marine scientist smiled bleakly. “As Mr. Hemingway would say, that’s not exactly a scientific term. But it’s accurate enough. Methane traps 22-times more solar heat than carbon dioxide. Similar undersea landslips triggered by volcanoes 55 million years ago released enough methane to raise temperatures 10 degrees in 10 years. The resulting runaway global warming lasted tens of thousands of years. Sea levels rose hundreds of feet. Most plants and sea life died. If Block 252 blows, planners I’ve talked to who are concerned with mega-disasters consider a sudden escape of methane hydrates on this scale to be comparable to an asteroid strike or nuclear war,” Huntington finished. “Jesus,” Hemingway said. It was not blasphemy but a prayer.

We came into the oil a few minutes later. The first small patch undulated on the water in a greasy stain a few hundred yards across. The second was slightly bigger. The next one stretched over the horizon. We couldn’t steer around it.

“There go the topsides and bottom paint,” Hemingway said as Pilar nosed into the mess.

“That admiral, what’s his name, Allen, said it’s hundreds of thousands of patches of oil all going in different directions,” I said.

The lighter compounds in crude used to make gasoline and plastics evaporate after a few hours. We were seeing what remains: a gooey tar-like residue filled with driftwood, plastic and other junk floating in the water. Hemingway stopped the boat while Samantha Huntington took pictures. She collected several samples and leaned heavily against the gunwale.

“I feel dizzy,” she said.

Hemingway was instantly concerned. It might be just the heat. If she was feeling the effects of the fumes, headaches and tremors came next, along with a rapid or irregular heartbeat. According to the MD he’d shared a few drinks with, unconsciousness and death could follow.

“I don’t know what we’re doing out here anyway,” Hemingway said. He started Pilar in a slow turn away from the slick. “It’s not like we can do anything.”

“Sometimes witnessing is all we can do.” Pilar’s new boatman had joined Hemingway and me on the bridge. The United Houma Nation native shook his head. “Indigenous people in southern Louisiana are among those hit hardest by the oil blowout,” the activist added. “We depend on fishing, which for us represents a connection to our traditional culture. Like our friends in Nigeria and too many other ripped-off places, we have suffered a long history of ecological injustice in this region.”

“You have already met my boatman, Clarence Freiloux,” Hemingway addressed us. “His community is Grandbois. There’s a big oil field waste site located right on its edge. Drilling fluids and other extraction by-products are taken there and simply dumped. Freiloux fought for years to shut it down. He finally reached an out-of-court settlement with Exxon, which manages the operation. Just before this happened.”

“This blow-out should be no surprise,” Freiloux said. “During its nine years at sea, the Deepwater Horizon suffered a series of spills and fires, even a collision before it finally exploded and sank, killing 11 crew. That is not unusual. Talk to Steve Sutton, the Coast Guard officer who oversees offshore drilling inspections. He will tell you that the number of accidents reported on the Deepwater Horizon did not strike him as unusual.”

“BP’s watchword is ‘reckless disregard’,” Huntington said.

“You got that right,” I said. “In March ‘05, corrosion in BP’s pipes caused the biggest spill ever recorded on Alaska’s North Slope. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration found BP in violation of more than 300 health and safety regulations and fined the company more than $21 million. That was the largest fine in the agency's history. Until 2007, when a BP refinery blew up and the company settled with the victims' families for $1.6 billion. The OSHA found 439 new ‘wilful’” violations by BP and fined the company another $87 million. But this was chump change for a company raking in $20 billion a year.”

I had everyone’s attention.

“By April this year, the Deepwater bore was taking longer to complete than expected. The rig, which BP was leasing from Transocean, was 43 days late for its next scheduled drilling location. BP was looking at $21 million in leasing fees when it decided to fast track their operation. I talked to roughnecks who saw internal memos from BP employees and contractors warning of an inadequate cement job. The well was deeper than anticipated and BP should have told Halliburton to change the cement mix to account for the higher pressures and colder water. They didn’t.

“Instead, when a Halliburton crew arrived to test the cement two days before the blow-out, BP sent them back. That decision saved BP more than $100,000 and several hours operating time. Company officials also ignored warnings of rising pressure in the casing and decided not to deploy a lockdown sleeve that would have prevented the seal from being blown out from below."

“Don’t hold your breath waiting for a criminal investigation,” Hemingway said.

Clarence Freiloux nodded. “Oil corrupts more than the ocean. In 2008, Obama actually took more campaign money from BP than his Republican opponent. As soon as he took office he ended a decades-long ban and approved deep offshore drilling up and down the Atlantic coast.

“Martin Feldman was the federal judge who lifted Obama's new six-month drilling moratorium. Judge Feldman has interests in Transocean and Halliburton, as well as two of BP's largest U.S. private shareholders, Black Rock and JP Morgan Chase. The law he overturned after Deepwater blew would have halted approval of any new permits and suspended deepwater drilling at 33 existing exploratory wells in the Gulf. Four of these are BP rigs.

“Transocean owns most of the world’s offshore drilling rigs, including the Deepwater Horizon. Thirty-seven of the 64 judges in key Gulf Coast districts have links to oil, gas and related energy industries. Many hold shares in BP, Halliburton and Transocean. There aren't enough untainted judges to allow the court to appeal lifting of the drilling ban.”

“And now,” Samantha Huntington said, “we find that the board supposedly studying the effects of the Deepwater Horizon ‘spill’ is being paid $10 million to come up with the right conclusions. Key congress people have been bought off. Senator Mary Landrieu assures us that the death cloud circulating far beneath the waves is irrelevant because we can’t see it. She claims that 97 percent of the blowout is ‘an extremely thin sheen of relatively light oil on the surface.’ Landrieu lies. From 2000 to 2008, she accepted $574,000 from Big Oil.

“Another Big Oil cash recipient is politician Gene Taylor. He calls what’s going down in the Gulf, spilled ‘chocolate milk’,” Freiloux picked up the conversational baton.

I nodded toward Freiloux. “We’re all natives of this planet. And there are no lifeboats. We ought to get together.”

“We got company,” Hemingway said. “Starboard quarter.”

* * *

We turned in time to see a bright red Zodiac with high freeboard and a pointy prow closing fast. A pair of spotlights and a radar dish adorned the Targa bar clamped like a big U-bolt over the hybrid craft. Its driver slowed sharply, coasting the rigid inflatable alongside.

“You folks on official business?” he shouted across.

“What’s it look like?” Hemingway called back.

“It looks like some old geezer in an even older tub with some people in a place they shouldn’t be.”

Hemingway’s eyes narrowed behind his dark Crookes lenses. “Who the hell are you?”

“BP security. Unless you got authorization, you folks are going to have to leave.”

Hemingway’s reply carried easily over the rumbling of Pilar’s engines and the Zode’s twin outboards. “Let’s see if I have this right. A British corporation is ordering Americans out of American waters. What are they? Still mad over our last tea party?”

“BP owns the oil,” the driver came back.

“WELL THEN THEY BETTER BY GOD CLEAN IT UP!” Hemingway roared.

The guard squirmed in his seat. “Ya’ll still need authorization.”

“I’ve got authorization,” Hemingway said. “Hold on while I get it.”

The kid looked skeptical. But he didn’t say anything. Ernest Hemingway clambered down the bridge ladder and disappeared below decks. A moment later the author reappeared brandishing a well cared for Thompson submachine gun. He drew back the charging bolt. The distinctive clatter was the sound of .45 calibre rounds seating home.

“Whoa! Is that thing loaded?”

Turning to face aft, Hemingway flipped up the safety and depressed the trigger. A dozen sharp geysers stitched Pilar’s wake in a huge rippling blast that laughed at Hollywood’s feeble sound effects.

“Seems to work,” Hemingway said into the stunned silence. “It’s hell on sharks,” he went on conversationally. “And it probably works just as good on smart ass kids who forget what country they’re from. Kids wearing rent-a-cop uniforms that don’t fit too well.”

The security guard’s eyes had become too big for his face. One hand reached sideways toward his walkie-talkie.

“Don’t,” Hemingway said.

The guard looked up into a still smoking bore roughly the size of a privateer’s cannon.

“Right,” he said, jerking his hand away from the radio. “I’m outta here. Sorry to bother ya’ll.”

“An excellent idea,” Hemingway said. “We were just leaving ourselves. You don’t want to breathe too much of these fumes. Makes people stupid.”

We watched the Zodiac roar off, pursued by its own private cloud of petroleum smog. Pilar’s compass card spun as Hemingway turned onto a reciprocal heading. Samantha Huntington felt guilty yet glad that they would beat the spill back to the Florida coast. Then she remembered that the much bigger underwater plume was already there.

The sun was in our faces now. Slanting up off the water, it stung Samantha's eyes under the long visor of her cap. She understood why Hemingway was wearing dark glasses with tinted side flaps that would not have been out of place on a melting Greenland glacier.

“Let’s go below and heat some chilli,” Papa said. “We haven’t eaten since breakfast.” Turning to his boatman, he instructed, “Synchronize your motors at three-hundred. When we come in sight of land I’ll give you a correction. Listen for it. Don’t just watch the tachometers.”

“East by nor’east. I got it,” Freiloux said.

In the galley off Pilar’s broad quarterdeck, I took the cans Hemingway opened and decanted their contents into a frying pan. The boat lifted and corkscrewed to the quartering swell. The skillet slid with a clang against the sea rails on the alcohol stove. Every time the boat rolled, the galley sink gurgled with the backwash in its drain. Braced easily in the nook between the counter and gimballed stove, Huntington handed Hemingway his favorite beverage. The glass came wrapped in a triple thickness of paper towel with a rubber band around it to hold the paper tight and keep the ice from melting.

“I put lime, bitters, and no sugar in it, just like you described in Islands In The Stream. Is that how you want it?”

“Best part of the book,” Hemingway said. “Too bad the critics missed it. That’s fine. Did you make it with coconut water?”

“Yes, and I made Mr. Guidry and me a whisky. Your boatman wants a Coke.”

“Thanks. I’ll bring it up to him.”

No one seemed concerned that Ernest Hemingway had been dead for nearly half a century. Or that the wheel inside the deckhouse was being turned by a ghostly hand. It spun briefly to port, then back the other way as Freiloux steered from above.

Hemingway took a swallow. He tasted the cold bite of the lime, the aromatic varnishy taste of the Angostura and gin stiffening the icy coconut water.

“Perfect,” he pronounced. He took another long pull. The horrors outside seemed to recede.

“At least it won’t burn off your taste buds like the time you mistook a bottle of Javex for Evian water at the Floridita,” Samantha Huntington said.

Hemingway laughed. “You’re right. This sure beats drinking concentrated lye. But when we get back in, who is going to believe we were ever out here? That kid in the Zodiac looked like he’d seen a Flying Dutchman.”

“Maybe he did,” I said. “It wouldn’t be the first time. In waters like these.”

Author’s Note:

Sitting in my easy chair reading Hemingway On Fishing after watching some of the Deepwater Horizon coverage, I suddenly sat up straight thinking, what if…

An award-winning investigative reporter whose writing and photography have appeared in more than 50 magazines in eight countries with translations into French, Dutch and Japanese, I have spent much of his life aboard small boats. In 1985, I completed an eight year Pacific circumnavigation by making the first nonstop passage by trimaran from Japan to North America. No stranger to oil disasters, I later served on a three-man environmental emergency response team in the oil-fed hell of Kuwait.

All details in this “trans-fictional” narrative relating to science, BP and political corruption come from mainstream published sources. In homage to Ernest Hemingway, the descriptions of Hemingway’s life, Pilar and deep sea fishing in the Gulf Stream are either quoted directly or adapted from Hemingway’s writing. Much of Hemingway’s dialogue is also his own words.

Clarence Freiloux is based on a real person and events. Samantha Huntington is a complete invention, though her scientific assertions are accurate. The remarks of both fictional boatmen are also factually correct. Their dialogue relating to Louisiana life and perspectives is quoted directly from contemporary accounts reported at the time of the Deepwater disaster.

As a writer over-fond of run-on sentences, I found writing in Papa Hemingway’s signature style challenging.

And instructive. -William Thomas

Photo Captions:

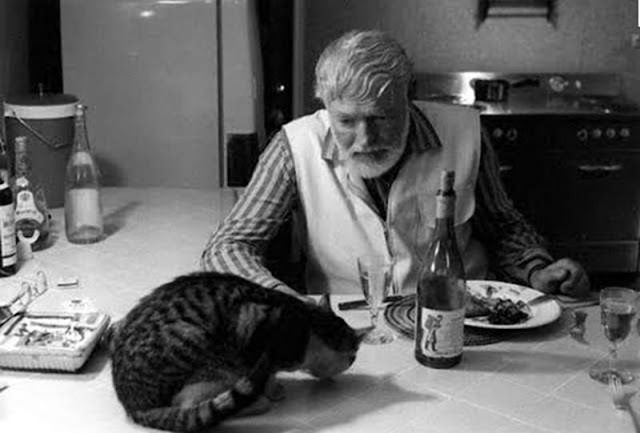

Hemingway cat comes to dinner -vintag.es

Large big swordfish athwart Pilar's transom -modelshipworld.com

Deepwater Horizon disaster -newyorker.com

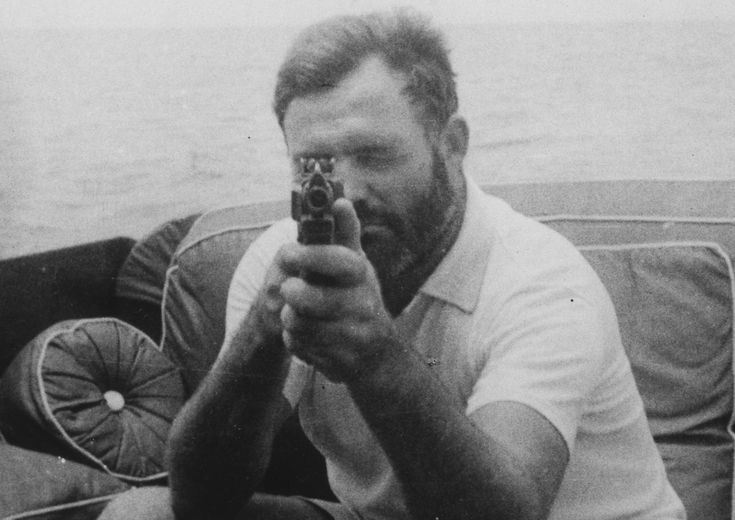

Meet Mr Hemingway and Mr Thompson

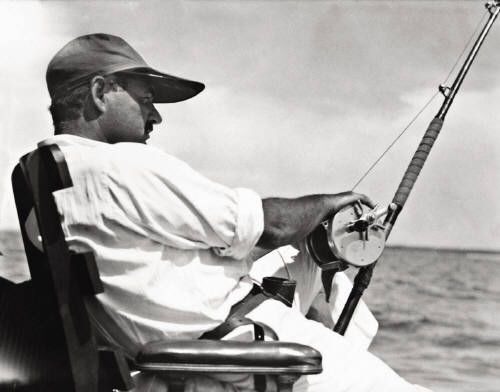

Pilar fishing underway -anglersjournal.com