IF LEE MET LINCOLN AT APPOMATTOX

IF LEE MET LINCOLN AT APPOMATTOX

by William Thomas

Lee —not “General Lee” just now, but for one brief blessed moment, only the “Lee” his dear wife called him— preferred the early mornings. Before the men stirred from uneasy slumber and gathered in small groups, some lighting pipes what had them. (No need for cooking fires for there was nothing to boil or fry.) So quiet, Lee thought. Soothing as Mary’s bosom, which he longed to lay upon again. If the Lord ever deigned to grant him such rest. Until their reunion, he knew, the guns would speak of their terrible need. And the butchery, so antithetical to womankind, resume.

Yes, this morning’s interlude was another blessing in a campaign that had seen little respite. Birds were singing their delight in another morning, as if they had never heard the cries of the maimed and thunderous engines of war. In these fleeting moments of nature’s glory, with The day’s first warm caressing breeze rattling leaves and stirring the tall grass, it was almost possible to think of peace…

Jingle of saber and saddle through the trees, followed by a cleared throat close behind. “Beggin’ the genr’l’s pardon. It is the time agreed upon.”

“Thank you, colonel,” Lee addressed his adjutant, turning around with a wan welcoming smile. “Let us proceed. Leave your sword and pistol and come forward with me.”

“Yessir. All the boys is a-waitin’, genr’l. Them murderin’ bluebellies try anythin’ and we…”

“Stand down, colonel. Mr. Lincoln is an honorable man.”

“Yessir.” Though this time, less promptly. And certainly less convincingly.

Breaking from the wood, General Lee held his twice-wounded Traveler to a slow, dignified walk. His frowning aide trailed some short distance behind, clearly unhappy with this scheme. On the field’s far end, a black coach, appropriately enough drawn by two black mares, approached as if it had been awaiting the Confederate cue. At its center, guerdons of both the North and South marked their rendezvous. The lone rider and car halted facing each other across a short stretch of ground.

Like some old testament prophet, Lincoln unfolded his improbable length from a borrowed conveyance never intended to shelter a scrawny giant. I’d like to wring this man’s neck with my bare hands, the president thought, measuring his opponent for all those long bloody years. But by God he can sit a horse.

Lee dismounted stiffly, handing over his reins.

A sabre’s thrust distant, Lee came to a boot-slapping halt and saluted. Lincoln nodded back, thinking, already this feels even more salubrious than First Manassas. Before either could speak, a mischievous gust whisked that trademark stovepipe hat off Lincoln’s unruly pate and sent it sailing toward the rebel mob. Surprising them both, General Robert E. Lee reached up without looking and snatched it from the air with one gloved hand. Bowing curtly, he handed it back.

Men at both ends of the field cheered.

“Why General Lee, that was well-played,” Lincoln said, accepting the return of his cover but making no move to further tempt indignity. “I believe that’s the term. Perhaps when this unpleasantness is over you can try out for our new sport. ‘Baseball,’ they’re calling it. Whatever that might mean.” The president tried a jest. “If you are as handy with that sword, should I fear for my life?” General Lee said nothing. Where was this man’s fabled propriety? Finally he replied, close-lipped, to this insult on Southern honor. “You are quite safe with me.” No honorific this time.

President Lincoln registered Lee’s tone. And his own error. This hard-bitten Virginian looking up at him like Jesus’ own judgement was utterly devoid of humor. Why wouldn’t he be?

“General Lee, I know I am,” he started again. “My apologies for my intemperate tone. It has been a trying time for us both.”

Lee nodded curtly.

“Please proceed with your parlay. I take it, you have come seeking terms of surrender.”

Lee reacted as if slapped. “Mr. Lincoln…”

“’Mr. President’ will do.”

“I fear, Mr. Lincoln, you are under some misapprehension as to my intentions for this meeting.”

Now it was Honest Abe’s turn to show surprise. “If not surrender, what then, genr’l? You have come, sir, to offer me terms? Perhaps to demand General Grant’s surrender?” The President of the northern not-entirely-united states permitted himself a quick, tension-dispelling chuckle. Which achieved nothing of the kind.

“An armistice, sir. I propose a general laying down of arms and an honorable pledge—on both sides—not to renew hostilities.”

“A mutual surrender without anyone actually surrendering,” the president clarified.

“There is no need to speak of surrender,” Lee pressed, as ramrod straight as his arthritis allowed. His white-gloved right hand rested easily on the tasseled pommel of his dress sword, which he’d been permitted to retain for the sake of dignity in front of his soldiers. The gesture was not threatening. More like someone touching a reassuringly familiar talisman while his entire world— everything he believed in and held dear—lurched and stuttered towards long-imagined yet unutterable ruin.

Lincoln’s temper, always quick to rise when sensing trickery among his own generals, took on a firmer tone.

“General Lee. Do you apprehend what lies out of sight behind those few observers arrayed on the ridge behind me? I refer to the men and machinery of war hidden from view below the military crest of that same rise. Certainly your scouts have appraised you of what awaits your army there.”

“Why I believe they have, sir. A Pharaoh’s legions. Tents and tethered horses to eternity.”

“As well as a dozen batteries of artillery and mortars. Fifty-thousand men under arms. With two more armies coming up to encircle this glade. If your brave men embark on a futile last stand I know we both want to avoid, they will, yes, unleash a final volley, causing yet more carnage among their fellow Americans. Then the survivors still standing amidst our counter-fire will spend another long minute ramming home another cartridge on top of the ones, in their excitement, many did not fire, whilst my most exasperated boys in blue will continue pouring unceasing volleys of massed carbines into their ranks.” Lincoln paused for effect. “Without pausing to reload.”

Repeaters, Lee breathed. As if naming the wrath if God.

“I am told we’ve even brought up a brace of Gatlings,” Lincoln went on. “I am sure you have encountered their unwelcome hellfire. Perhaps more than oncet.”

General Lee’s eyes showed that he had.

“Now kindly turn and inspect your scarecrow army.” Adding quickly, “A simple point of fact, general. I mean no disrespect.

Lee waited. Lincoln did like to jaw.

“Except for the remnant still futilely fighting out West— Farragut’s control of the Mississippi and our seizure of all rail lines west ensure them no more supplies. Except for those last, cut-off holdouts, your entire army occupies the far end of this well-trampled field. And as you have already observed—for you are a fine student of ground, as we have learned to our cost, trained by our best at West Point, then commendably honed under fire while in federal service in Mexico. Even I can see there is no cover for a field mouse marching at the quick step across this expanse.”

The president did not have to voice his thoughts of Gettysburg and Pickett’s stirring doomed trek through an afternoon of cannonballs, grape and enfilading musket fire. He could see the general standing across from him had also journeyed back there. Remembering. Comparing. Any assault attempted here against the Yankee lines would be a brief bloody parade.

Lee did not turn. He did not have to. He had scanned this potential killing field and his “scarecrow army” as his beloved white charger stepped from the wood. A thousand men under arms. Maybe. Footsore. Racked by rickets and the onset of scurvy. Unable to recall their last meal. Proud. Stubborn. Defiant. With powder and ball for perhaps two volleys. No more.

“Desertion is thinning your ranks even faster than our howitzers did,” the president went on. Not in boast, but quiet reminder of an impossible situation. “What do you suppose would happen if I ordered a battalion forward to start cooking coffee and bacon atop that rise?”

My boys would break ranks and enjoy a good breakfast, Lee thought. And was instantly shamed. Aloud he said, “I did not take you for a cruel man.”

“And I am prepared to be magnanimous,” Lincoln said without smiling. “But let us hear no more talk of ‘armistice’. Your side started this rebellion, general. And by God, this army will finish it here—today—if that is your wish. Though I see no glory in it.”

Lee remained silent, thinking of Yankee invasions, scorched earth. The lasting bitterness of defeat.

Reading this, Lincoln tried once more. “Come, general, the end is in plain view. Let us cease this terrible bloodletting. Here. Today.”

“Now you are offering me terms,” Lee managed, as if swallowing a hearty sip of lye.

“That I am,” said Abe Lincoln.

“And those terms are?”

“They are most generous, general. Out of respect for their valiant fight, after signing the parole you have already suggested, every man under your command will be allowed to return home with their musket and horse or mule. It’s harvest time. The South is hungry.”

Because Sherman has burnt those secessionist states to the ground, both men thought at once.

“These implements will come in handy in the days and weeks ahead. As will your men’s presence—honorable presence—at home.”

“And myself, sir?”

“My generals and advisers want to try you for sedition and see you hang.”

Lee stiffened. A sharp-eyed corporal at the Confederate end of field jumped to his feet. Said, “Hey, boys.” And the men around him rose as one in rags of butternut, gray and blue and started for the muskets stacked a hundred paces to their rear. At this, more of their comrades began to rise also. Until sergeants barked orders. And the entire assembly begrudgingly sat back again. Or sprawled on in the dusty grass as if shot down at last.

“Plenty of spark left in your boys,” Lincoln turned back around to compliment his opponent. “And I do not doubt their desire and ability to inflict further hurt on my boys. Before they are winnowed like wheat in fields better served by applying plows. Will you harvest the grain of life, General Lee? Or the blood and gristle of more wasted lives”

A sigh shook Lee’s body in a withering volley of grief for the South he had lost. And might yet regain. But only under the Stars and Stripes of the hated despoilers of this sacred soil.

Before he could respond—if he could respond—Lincoln said, “General Lee, I am told you have freed your house and field slaves. With such a fine example, is it not time the South followed your lead?”

“And the North, as well.” Lee spoke at last.

Lincoln darn near gaped at him. Instead, he said quietly, “And the North, as well. Let us abolish this wicked sin together for once and all.”

As if awakening from the lingering spell of war, both men fell silent. As did the birdsong. Indeed, the world seemed to hold its breath. Would stubborn pride win out? Would a slaughter such as never had been witnessed on earth play out its final momentum and resume?

As the moment stretched toward some awful denouement, and Lee’s countenance flickered between resignation, loss, and renewed revolt, Lincoln felt the first stirrings of fear. Before the rebel leader could utter a last act of defiance that would not only martyr the remnants of his army but any hope for the peace that might—had to—follow, the president spoke.

“General Lee, with respect for your men and a fight well fought, do not answer now. There is a humble but well-kept courthouse not far from here. At a place called Appomattox.”

“I know that place,” Lee said in a voice grown suddenly and permanently old.

“The owner, who moved his family out here to be safe from war, has agreed to its use. Think on our conversation. And if it is agreeable to you, send a runner under white flag before noon tomorrow, and we will meet there amicably to sign the terms I have outlined.”

Lincoln wanted to add, I personally guarantee that your army will be treated with respect. Your men will be fed and their wounded tended. No one, including yourself, will face a prison cell once your paroles are in hand. But he forebear making an offer that—until the final papers were proffered and signed—would be taken as a slur and a bribe.

Lee spoke. “Sir, I am relieved to hear there will be no further bloodshed today. Let us see what the good Lord wills and the morrow may bring.”

Lincoln considered this. “General, have you ever pondered how it is we both pray to the same God for victory?”

Lee had. Often.

“I leave those questions to Him, sir.”

“Yes. Well. I just wish He had made up His mind four years sooner.”

“We are but instruments of His will, sir.”

Weak, vain, imperfect instruments at best, Lincoln thought. But for once he kept his remarks to himself.

“Very well, general. I shall await your reply.”

Again, Lincoln bowed briefly, a courteous tip of his unshod head. Lee snapped off a crisp salute, performed as smart an about-face as his old bones permitted, and strode back to his horse. The meeting was over. An armistice was not signed. But as if sensing change in the air, songbirds broke into louder chorus. And for the first time in a very long time, the day promised fair.

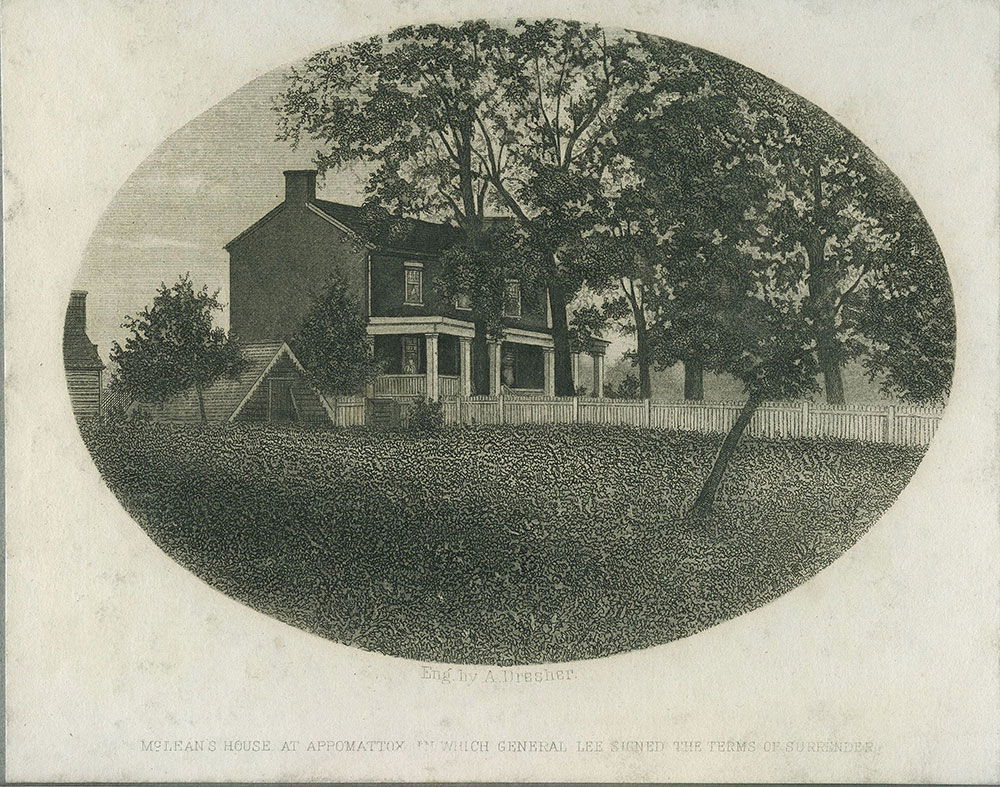

Photo Caption: McLean's House at Appomattox in which General Lee Signed the Terms of Surrender